Fostering Free Expression

Tom Ginsburg grew up in Berkeley, California, in the years after the free speech movement swept the UC Berkeley campus. As a child, he’d hear about the importance of free expression from those who took part in the movement, especially his father, and learned to speak freely, question his own knowledge, and listen closely to those with whom he disagreed.

The afterglow of those protests for academic freedom lit the path of his career in law and academia. Ginsburg was fascinated by the role of free expression in a democratic society. Today, he’s one of the world’s most widely published and respected scholars of democracy.

But lately, Ginsburg has felt concerned about the future of academic freedom. In the United States, where freedom of speech is cemented in law by the First Amendment, people have grown cautious in what they express, often to the point of self-censorship. Fear of reprisal from others who disagree with them is a driving factor, according to a poll of more than 1,500 US residents by the Sienna College Research Institute and the New York Times. This poll found that 55 percent have not spoken freely at some point in the past year due to concerns over potential retaliation or harsh criticism. And this fear is greater for younger Americans, the poll found, as 61 percent of people ages 18 to 34 said that they’ve held their tongue over the past year.

“I don’t think you can have free societies without free universities.”

Tom Ginsburg

A combination of social media, the prominence of live cameras, and the trend of vast public scorn for private citizens has led to more self-censorship. But self-censorship means that fewer ideas are being publicly debated in good faith. As this trend grows, good ideas go untested, bad ideas go unchallenged, and a free society feels more restricted.

“Everyone thinks that everything they say and do is going to be broadcast and out there forever,” said Ginsburg, the Leo Spitz Distinguished Service Professor of International Law at the Law School. “That leads people to be reluctant to speak. That, of course, is something we must overcome.”

Aside from self-censorship, the threat of governmental and administrative censorship looms over universities. Ginsburg says that universities are often the first to feel pressure when free expression is under threat, which may look different depending on location. In the United States, universities may see state budget cuts or policy changes in response to forms of expression found unfavorable by those in power, especially in a polarized political climate. But in countries with little or no protection of free expression, consequences can be far more dire. Sulak Sivaraksa, a professor in Thailand and one of Ginsburg’s mentors, was recently arrested for insulting the king. The perceived insult? An opinion Sivaraksa had about a battle that occurred more than 500 years ago.

“I’ve noticed that universities are pretty vulnerable to attack, and not very well equipped to withstand it,” Ginsburg said. “I don’t think you can have free societies without free universities. Democracy needs truth-telling institutions.”

Launching the Chicago Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression

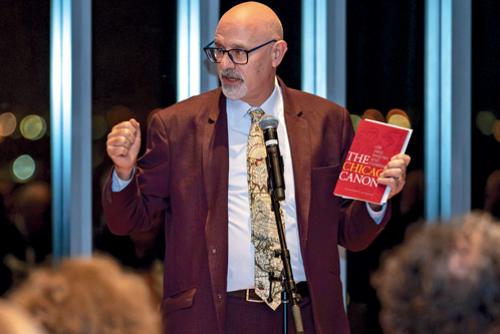

Last year, University of Chicago President Paul Alivisatos took Ginsburg out to breakfast, where he asked if Ginsburg wanted to be the faculty director of a new University initiative called the Chicago Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression. The Chicago Forum would promote the understanding and practice of open discourse at UChicago and beyond.

Ginsburg, whose recent book Democracies and International Law had just won the American Branch of the International Law Association’s 2022 Book of the Year Award, thought the forum sounded like the perfect way to continue his life’s work.

“I thought about it for about five seconds and then said ‘yes,’” Ginsburg said.

Given his legal scholarship, Ginsburg seemed the right person for the job. But he had also been honing practices of free expression with students at the Law School, providing opportunities to have discussions on complex, controversial topics. For example, Ginsburg would have students discuss what separates hate speech from free speech. Who decides what becomes hate speech, and how it is punished? Ginsburg wanted future attorneys, who will have to deal with a career full of disagreements, to become comfortable with sharing differences of opinion in a low-stakes learning environment without fear of public scorn. “Part of the way to construct the environment is to insulate them from social media,” said Ginsburg. “That’s one of the things we have to do to get this right.”

Ginsburg also started a series of roundtable lunches in 2015 just before Donald Trump was elected as US president. The anger level on campus had risen, and Ginsburg wanted to find a way to cut through the anger by allowing students to debate and learn about ideas from multiple perspectives. During these lunches, professors would take opposite sides of an issue and, along with students in attendance, discuss each side’s positions, searching for common ground. “It was really fun,” Ginsburg said. “My colleagues loved it, because that’s what we do all day anyway.”

Last year, Ginsburg presented at orientations about the University of Chicago tradition of free expression for divisions across campus, engaging with them on why it’s essential to academic freedom. For example, he hosted an orientation event for the physics program to discuss differences in opinion on climate change. “They’re confronted with some cases where there are really deep divisions,” Ginsburg said.

Ginsburg hired Tony Banout—who earned his PhD in political and religious philosophy and ethics from UChicago—as the Chicago Forum’s executive director. Both have been working closely to build the forum, which publicly launched in October with a series of in-person panel discussions. Soon, the forum will offer academic grants and fellowships, as well as host more discussions, including the Academic Freedom Institute, planned for 2024 and designed for academics and administrators in higher education.

Geoffrey Stone, the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law and a nationally renowned free speech expert, says that the Chicago Forum exists on the premise that free speech is a force for good. Amid a moment when free expression is chilled, Stone says that the forum could help give people the tools to reengage in their own forms of free expression.

“Part of the idea is to figure out how universities can be more effective at encouraging students and explaining why freedom of expression is important,” Stone said. “Even when the ideas someone is articulating are things you strongly disagree with, they should be allowed to do that.”

The Law School’s History of Free Expression

When William Rainey Harper was named the University’s first president in 1891, he brought a then-unorthodox style of open scientific inquiry. This philosophy of open inquiry served as the foundation of UChicago’s rich history of free expression. Harper said in 1902 that free expression is a fundamental part of UChicago and that “this principle can neither now nor at any future time be called in question.”

And while other universities have, at times, wavered in their support of free expression, UChicago has always stood behind it, even amid painful moments. In 1932, the University drew public ire for inviting a presidential candidate from the Communist Party to speak. Robert M. Hutchins, then president of UChicago, responded to the backlash by saying that the cure for ideas we oppose “lies through open discussion rather than through inhibition.” In 1967, when universities felt pressure to take stands on social and political issues, the University released a statement drafted by a committee—chaired by Law School professor and First Amendment scholar Harry Kalven Jr.—stating that if UChicago took any collective position, it would be akin to censuring those who disagreed with that position.

“The neutrality of the university as an institution arises then not from a lack of courage nor out of indifference and insensitivity,” said the statement, which came to be known as the Kalven Report. “It arises out of respect for free inquiry and the obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints.”

In the 2010s, campuses nationwide saw an uptick in interruptions and disinvitations of speakers. At UChicago, professors from the Law School were tapped to serve as chairs of committees that examined how its historic commitment to free expression could be renewed and strengthened within the challenging moment. Under the leadership of Law School faculty members, each of these committees crafted influential reports on free expression.

“Part of the idea is to figure out how universities can be more effective at encouraging students and explaining why freedom of expression is important.”

Geoffrey Stone

David Strauss, the Gerald Ratner Distinguished Service Professor of Law, served as committee chair for the Ad Hoc Committee on Protest and Dissent, which was created in response to demonstrations and controversy taking place at the University of Chicago Medical Center. The committee’s report affirmed that dissent and protest are integral to the life of the University. Its recommendations included a limit on protest that threatens sensitive facilities as well as minimal police involvement in protest whenever possible. The report also suggested introducing students to specific policies that govern protest and debate.

Later that year, Stone chaired the Committee on Freedom of Expression, which produced a report that came to be known as the Chicago Principles. The report laid out how the University has and will continue to treat free expression: debate is welcomed, students can vigorously discuss even the most offensive ideas, and it is not the University’s place to judge student’s ideas nor suppress their speech.

“It was an effort to articulate clearly what has long been the tradition and values of the University,” Stone said. “It wasn’t meant to change anything. It was meant to simply articulate what have long been our institution’s values and goals. What makes UChicago special is that in all historical circumstances, it has backed the principle of free speech and supported students, faculty, and speakers in their ability to set forth what they believe to be appropriate positions, even though many members of the faculty, the student body, and the community might not agree. We were unique and powerful in doing that.”

Though the Chicago Principles were meant for UChicago, other universities took notice. They too had felt heavy pressure to make statements on political and social issues, watched an increasing number of campus protests, and heard demands from students to suppress certain forms of expression. Quickly, many other universities adopted the Chicago Principles for their own campuses. In 2015, Princeton University was one of the first to adopt them, using the Chicago Principles as the starting point for their own Princeton Principles for a Campus Culture of Free Inquiry. The Princeton Principles, written in 2023, say that “universities have a special fiduciary duty to foster freedom of thought for the benefit of the societies that sustain them.” Now, nearly 100 other universities have adopted the Chicago Principles. In addition, the American Bar Association is considering whether it should amend its law school accreditation standards to adopt the Chicago Principles.

In 2017, the third UChicago report on free expression came via the Committee on University Discipline for Disruptive Conduct, chaired by Randal Picker, the James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law. Picker says that he and members of the committee had watched on, in horror, as other campuses experienced violence amid protest. He hoped that his committee’s report could transparently explain rules for engagement for student protest while avoiding punishment, violence, and destruction.

The Disruptive Conduct report listed a series of framing principles for student disciplinary matters—those who disobeyed could be disciplined. Students are within their rights to protest and object to speech, the report said, so long as they don’t block or disrupt the ability of others to speak or hear a speaker. This rule combats what Kalven called the “heckler’s veto,” where a speaker is silenced, drowned out by noise, or threatened to the point of no longer speaking. The heckler’s veto has recently become a common tactic used by protestors who want to shut down controversial speakers.

“Making sure that students understand the rules of engagement and their shared obligations has been key.”

Randal Picker

“That’s a free speech failure,” Picker said. “[The Chicago Principles] are a broad statement of philosophy. With this committee, we wanted to try to build a regime of education in which we get those principles vindicated. If there’s disruption and a need for a disciplinary regime, OK, we’ve constructed that too, with people trained to make difficult choices. But really, this report is about vindicating speech.”

By the time the Disruptive Conduct report was being written, the Chicago Principles had received national coverage and been adopted by multiple universities. This meant more eyes and more scrutiny on Picker’s report, both while drafting the report and after it was released. But those additional eyes seem to be a good thing for campus protest. Thus far, Picker says there has been little use of the Disruptive Conduct Committee to discipline students, as most have learned the distinction between protest and disruption, including intimidation, violence, or the heckler’s veto. In fact, Picker has seen students who created signs with footnotes citing his report, stating their right to protest.

“That’s fantastic,” Picker said. “You stand at the back, you hold up your sign, and you say what you want on that sign. That’s perfect. It’s a way for people to convey their disagreement with the speaker while still allowing the speaker to speak and the audience to hear. Making sure that students understand the rules of engagement and their shared obligations has been key to this, an education process led by University Dean of Students Michele Rasmussen.”

Picker considers the Chicago Forum to be the next chapter in UChicago’s commitment to free expression, following the four faculty committee reports. Those first four reports outlined the principles and rules of free expression for UChicago, Picker says, while the forum has a chance to teach people how to engage in robust speech within a pluralistic society, both on and off campus. This is essential for bringing a strong culture of free expression into the future, Picker believes.

“What you need is to have a society where people are exposed to competing views and be willing to think about them. That requires a lot of education, particularly beginning with young people.”

Geoffrey Stone

“Culture is hugely important,” he said. “I’m part of a shared culture and I benefit from it; therefore, I have an obligation to help preserve it. That says nothing about what substantive positions you take, but the nature of engagement, especially engagement with people who disagree with you.”

The Future of Expression

Part of becoming a great thinker is the ability to debate ideas, Ginsburg says, even taking sides you don’t believe in. Attorneys know this well—the Law School has been the backbone of free expression at UChicago because attorneys are trained to argue, even on the side of clients whom they may privately believe are guilty. After all, everyone deserves a vigorous legal defense.

But the Chicago Forum will reach outside the Law School and even outside UChicago, Ginsburg says, as thinking people must be able to express ideas—even unpopular ideas—and hear criticism, even when it stings. With more younger people feeling the fear of what happens if they say the wrong thing, he wants to be proactive and positive in teaching free expression and why it is essential to society, showing that it is sometimes essential to speak freely through the fear.

“I don’t think ‘free speech’ quite captures what this is about,” Ginsburg said. “It implies a sense of constraint; if we get out of the way, all of this good speech is going to happen. But I don’t see that happening in the world. We need to provide environments and opportunities where students can experiment more.”

According to Ginsburg, the fundamental reason universities care about free expression is because it is essential to inquiry and knowledge creation. If certain topics or conclusions are taboo, learning is stunted. The best opportunity to learn is having a diverse group of people who are willing to listen to one another, have deeper conversations, and speak without fear of retribution. And Stone agrees, saying that these kinds of collaborative but difficult conversations have often changed history.

“If we didn’t have a very strong commitment to free expression in our country, we wouldn’t have had interracial marriage, we wouldn’t have had same-sex marriage, and we wouldn’t have had laws guaranteeing equal rights,” Stone said. “These were all the product of people being willing to stand up and talk about issues that were regarded as highly controversial. It takes courage to do that. What you need is to have a society where people are exposed to competing views and be willing to think about them. That requires a lot of education, particularly beginning with young people.”

As the leader of the Chicago Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression, Ginsburg hopes to inspire students to think and speak freely, rather than focus on winning an argument. He wants to teach students to have conversations that build their knowledge and understanding of the world, just as he was able to do as a student.

“We want to be a place that involves every student in the University, that allows them all to come away feeling included, able to voice their opinions, and develop their views in a healthy way,” Ginsburg said. “That’s the goal.”

Hal Conick is a freelance writer based in Chicago.