Law School Faculty Shaping the Law with Their Ideas

Curtis Bradley could barely believe his eyes. While reading a draft of a 2022 appropriations law being proposed to Congress, he noticed that it seemed to be codifying what he and two coauthors had argued in a paper, nearly point by point.

Two years ago, Bradley and two coauthors—Yale Law Professor Oona Hathaway and Harvard Law Professor Jack Goldsmith—wrote that the executive branch had been failing in its duty to be transparent with executive agreements. These international agreements, which cover a wide range of commitments to other countries, were legally required to be reported to Congress and made available to the public, but many were being kept secret. The executive branch was also skirting approval of these agreements by Congress and the Senate.

The trio had worked hard on that paper, titled “The Failed Transparency Regime for Executive Agreements,” published in Harvard Law Review. They sued the US State Department to fulfill a request for documents under the Freedom of Information Act. From an examination of those documents, they found that a majority of the agreements were not being published and that about 20 percent lacked any plausible legal authority. The paper caught the attention of policymakers, who liked it enough to insert its proposals into the law.

Bradley, the Allen M. Singer Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School and an expert in US foreign relations law, had spoken with policymakers for years and even served on a State Department advisory committee. But seeing policy recommendations he advanced in a scholarly paper written into a law felt almost surreal. If the draft was passed as is, it would mean sweeping changes to transparency requirements on executive agreements—it would also mean that nearly everything proposed in that paper would be law.

But Bradley and his coauthors, after reaching out to people behind the scenes, felt skeptical that the draft would be passed without serious revisions. They heard that the State Department disliked the section of the bill inspired by their paper, and Bradley could see why. The changes proposed in the law, although in line with the spirit of the current law, would create a mountain of new work for State Department employees. Bradley said that he wouldn’t have been shocked if the language was removed from the bill.

Then, something incredible happened: The law passed. The section Bradley and his coauthors had inspired was left intact. In December 2022, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 was signed into law by President Joe Biden. The new transparency requirements for executive agreements, which include much broader reporting and publication requirements, will take effect in September 2023.

“We were thrilled—we’re still very pleasantly surprised. Most of what we had proposed in the paper is now law. That’s very gratifying.”

Curtis A. Bradley

“We were thrilled—we’re still very pleasantly surprised,” Bradley said. “Most of what we had proposed in the paper is now law. That’s very gratifying.”

Bradley’s years of experience as a researcher and professor led to a real change in US law. And he’s not the only professor at the Law School whose expertise has influenced the government.

Context Over Contention

In early 2021, Alison LaCroix received a call from Yale Law School Professor Cristina Rodríguez. Rodríguez wanted to know if LaCroix—the Robert Newton Reid Professor of Law at the Law School—would be interested in joining a commission that would analyze issues surrounding the Supreme Court of the United States.

The public conversation on topics like term limits and court packing on the Supreme Court had been heating up, with the most polarized opinions spoken loudest. Biden wanted to assemble a group of scholars that would give a fair, cool-headed analysis of the issues facing the Court. LaCroix, a lawyer and historian who focuses on constitutional law and history, felt excited by the idea, as she had never been involved with the government in this way. She agreed to join.

In April 2021, Biden issued Executive Order 14023, which formed the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States. This was to be a bipartisan group of experts on the Court and its reform debate. The Commission was instructed to provide analysis on topics like size of the Court, length of service for Supreme Court Justices, and the Court’s role in the Constitutional system, then produce a wide-spanning report that would inform readers on these issues.

“I always wondered if there were ways to make an impact beyond writing and teaching. This Commission felt like a chance to really have serious historical insight brought into the conversation on the Supreme Court.”

Alison L. LaCroix

“When you teach in a law school, you write, teach, and do a lot of research,” LaCroix said. “But I always wondered if there were ways to make an impact beyond writing and teaching. This Commission felt like a chance to really have serious historical insight brought into the conversation on the Supreme Court.”

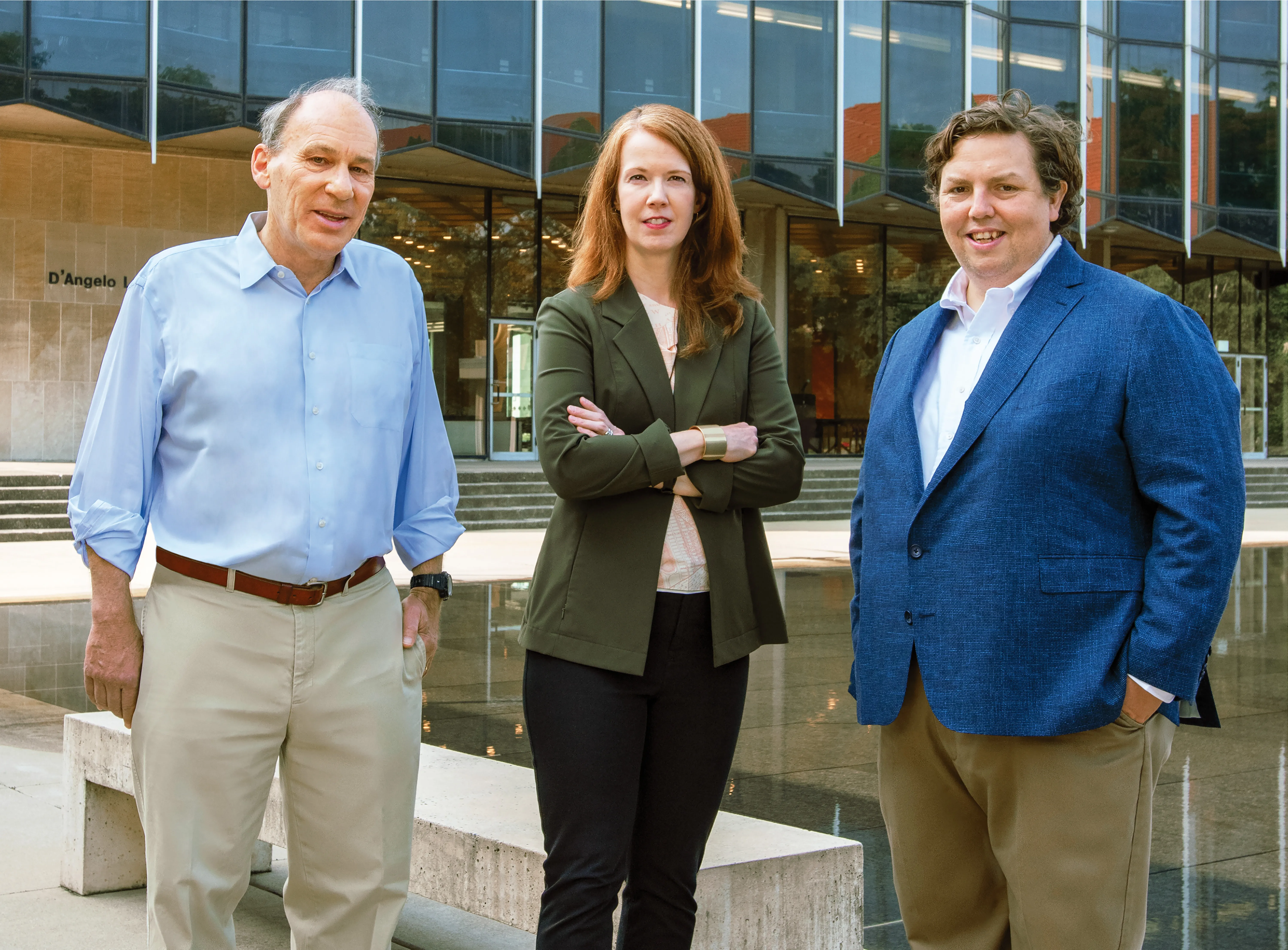

The Commission consisted of 34 scholars from universities across the US, including LaCroix and two other professors from the Law School, William Baude and David Strauss. Baude is the Harry Kalven, Jr. Professor of Law and the faculty director of the Constitutional Law Institute, while Strauss is the Gerald Ratner Distinguished Service Professor of Law and the faculty director of the Supreme Court and Appellate Clinic. None of the three Law School professors had ever served on such a commission, but all were proud to be invited.

Meeting publicly over Zoom, the commissioners listened to each other’s viewpoints, discussed historical context, and worked on a report they hoped would be clear and cohesive. The group of experts would often break off into smaller groups, discussing specific issues in their areas of expertise. Some brought their work back to campus—Baude recruited student research assistants to help him prepare for work on the Commission.

Working with such a large group of scholars, especially to write a cohesive document, felt like a challenge to the Law School professors involved. Professors are used to writing alone or on teams of two or three people but writing as a group of more than 30 experts felt quite difficult. Strauss wondered early in the process how a commission of this size would operate: Could they really meet a deadline for a report without ever meeting in person?

“I was pleasantly surprised by how thorough, comprehensive, and helpful the report was. . . . I’m honored to be part of it.”

David A. Strauss

Meeting publicly, a legal requirement, made working on this report even harder, according to Baude. “In law school, you learn that you’re supposed to ask questions without an agenda,” he says. “Those norms don’t really translate to this environment, which is unfortunate. I think it completely changed everybody’s behavior. Nobody was behaving the way they would if there hadn’t been cameras in the room.”

But the group found its way through the challenges. Eight months after forming, the Commission produced a report that satisfied Strauss, Baude, and LaCroix. “I was pleasantly surprised by how thorough, comprehensive, and helpful the report was,” Strauss says. “It turned out to be a good piece of work. I’m honored to be part of it.”

Although Baude disliked aspects of the process, he has found the finished product useful. Since the report was published, he’s been using parts to guide class discussion and give students greater context on the Supreme Court. Baude believes that this report has potential to help anyone learn about the larger conversation behind the Court in a factual, even-handed way, without relying on opinion or misrepresentations of fact.

For LaCroix, being part of a group of experts brought together by a sitting president to provide context on the Supreme Court felt momentous. The process felt especially exciting when she had a copy of the finished report in her hands.

Still, LaCroix feels frustrated that the conversation is still so polarized, while the report isn’t more widely read. “Especially now, in the last couple of months as we’ve seen this discussion about the Court and ethics concerns,” LaCroix said. “There’s a whole section of the report talking about judicial ethics. It’s a little frustrating to me that we have this incredible resource that these 30-some experts spent all this time working on. Every time I see a news report, I feel like people could be more informed about the topic. I’d like it to be more available.”

Frustration aside, LaCroix felt happy to be part of a group of scholars who worked to provide context amid a moment of polarization. This is especially important for a topic like the Supreme Court, LaCroix believes. The truth, with context, tends to lower the temperature of a heated moment.

“Historical context helps mediate between those two poles,” LaCroix said. “I’d like to think that, even though it feels like we’re at this particularly contentious moment, something productive will come out of it.”

A Public Service

About a decade ago, Eric Posner became fascinated by how antitrust law is enforced in the labor market. He’d read about the illegal or shady actions of companies—such as Silicon Valley tech companies agreeing not to hire each other’s software engineers or fast-food companies entering into no-poaching agreements—and wrote papers on the legal, ethical, and societal implications.

His fascination led Posner, the Kirkland & Ellis Distinguished Service Professor of Law at the Law School, to write a book titled How Antitrust Failed Workers. The book argued that antitrust law has rarely been used to help workers, but that it should be strengthened in labor markets to help workers more often. This, Posner believes, would be beneficial for the economy.

Posner’s book caught the attention of people in policy circles during a time when Congress, the Justice Department, and the Federal Trade Commission were holding hearings on antitrust law. “I testified,” Posner said. “I spoke to some of the people in the FTC, some staffers in Congress, and other sorts of policymakers in Washington. And after Biden entered office, I was contacted by the Justice Department.”

Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter of the Antitrust Division invited Posner to join the division and Posner agreed, joining the Antitrust Division as counsel, a political appointee. He continued working at the Law School at the same time, often working for the Antitrust Department remotely from Chicago during the tail end of the pandemic’s lockdown days.

Posner’s main job was investigating companies that were suspected of violating antitrust law. “Or often, the Justice Department has to do an investigation when a corporation wants to merge with another corporation,” Posner said. “You’re looking at the behavior of the companies, their attributes, how big their market share is to see whether their merger is violating antitrust law.”

He also worked on antitrust litigation and what he called policymaking, guiding people on what is and is not legal under antitrust law. “Part of my job there was to help out with thinking through how these issues, as a labor market, had to be addressed,” he said.

This wasn’t Posner’s first government job, as he previously worked in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel 25 years ago. After lockdowns ended, he sometimes traveled to Washington, D.C., to work. The Antitrust Division was in the same building in which he had worked years before and he saw that nothing had changed. “Plumbing fixtures in the bathrooms are exactly the same,” Posner said. “In fact, they probably haven’t been changed in 100 years.”

Similarly, Posner said that the government and its legal practices often change slowly. It’s sometimes hard to see progress, Posner said, but he feels optimistic that the government will be able to bring more antitrust cases that will help workers.

Posner was happy to lend his expertise to the government and enjoyed gaining a greater understanding of the law by working with its enforcers. In the Antitrust Department, Posner wrote memos, asked questions, and spoke with people amid their own investigations to hear their perspective and make suggestions. It became a relationship where both sides learned.

“I think that was helpful for them,” Posner said. “And in return, I learned a lot about what the opportunities were for bringing lawsuits and helping companies improve their practices so they wouldn’t violate the law. That was rewarding for me.”

For Posner, working for the government as an antitrust investigator felt like doing a public service. The Antitrust Division alone has 600 lawyers, the size of a large law firm, but the Justice Department has about 10,000 lawyers and 100,000 employees, much bigger than any law firm. This gave Posner an opportunity to work with several different people each day, all of whom felt like they were on a similar mission to do a public service.

“They feel like they’re doing something that’s good for the country, and that’s a big boost for their morale,” Posner said. “It’s nice to be around people like that.”

“I spoke to some of the people in the FTC, some staffers in Congress, and other sorts of policymakers in Washington. And after Biden entered office, I was contacted by the Justice Department.”

Eric A. Posner

An Essential Relationship

After the work of Bradley and his coauthors led to a real-world legal change, he believes that his job as a researcher will become easier. When the new transparency laws for executive agreements go into effect, Bradley will have more access to documents that are typically hidden, allowing him to write and research with more depth. While he’s sure that this new law will bring its own set of challenges, those challenges will simply be another rich topic to research.

Beyond the real-world changes, Bradley believes that the relationship between the government and academics is essential to a strong legal system: through this relationship, Congress benefits from academic expertise, and legal academics benefit from understanding how government works. Even the State Department, later opposed to the changes brought about by Bradley’s paper, gave pre-publishing feedback that made it stronger.

“I run conferences on policy topics and try to involve people from government,” Bradley said. “They can come and hear from academics, but they’re often very open about their own views.

Sometimes they see things that academics don’t see, and they understand the pragmatic limitations of the law in ways that academics don’t. We don’t have to negotiate with other legislators on these issues and navigate a complex bureaucracy like government lawyers do.”

The relationship between a university and the government can be symbiotic, Strauss said, recalling his days of working as a government employee (before joining the faculty, Strauss was Assistant Solicitor General of the United States where he made many Supreme Court arguments, and before that, Attorney Advisor in the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Policy). Then, Strauss would find interesting problems, but he knew that there was no time to get caught up in theory when there was a deadline to write a brief. Now, as an academic, he spends his time digging into interesting legal problems, mostly unaware of what day-to-day challenges they present to attorneys in the field. By working together, Strauss said that government and academics can bridge the gap between their focuses and help each other come to a greater understanding of the law. “That kind of interaction can be tremendously valuable,” he said.

A relationship between the US government and a university also brings a sense of prestige and pride to campus. LaCroix loves that so many members of a small faculty have been able to make a real-world impact through government work, and she loves that it became a point of pride for students.

“The day the announcement that I was on the Commission finally came out, I was in class on Zoom and we were on a five-minute break,” LaCroix recalled. “When the class was back, I had messages from students congratulating me. It made me feel good that the students saw that their professors were participating in government and trying to make things better in a serious, rigorous way.”

“We’re actually trying to get clear about how the law works. That kind of perspective and expertise can really contribute to good governance.”

William Baude

For Baude, the experience of working as part of the Commission has been helpful for him as a professor, giving him a first-hand look at how the government operates. And by serving on the Commission, Baude believes that he and the other Chicago professors are sending an important message to the University community.

“It’s not that we just go into our offices and think about these things for fun, although it can be fun,” Baude said. “But we’re actually trying to get clear about how the law works. That kind of perspective and expertise can really contribute to good governance. And that turns out to be something that the government needs to function. We can show that to students, alumni, and the whole community.”

Posner believes that his work with the Antitrust Department, which ended in early 2023, has improved his teaching, especially his antitrust law class. “There’s a more natural feeling to teaching a class when you’ve been involved in the actual activity for a long period of time,” Posner said. “You’re not just reading the cases and discussing them with the students, you’re telling the students what actually happens. And they learn the law much better.”

“It made me feel good that the students saw that their professors were participating in government and trying to make things better in a serious, rigorous way.”

Alison L. LaCroix

Working with the government has also expanded Posner’s network, and thus the network of his students. While working in the Antitrust Division, he discovered that the government officials consider it part of their duty to speak with students at law schools. Before learning this, Posner had assumed that they’d be too busy to come speak to his classes—now, he’s actively trying to develop more interaction between his students and government officials.

“A couple of them visited last year,” Posner said. “Because I know these people now and I know how their division works, there will be a lot of opportunities for helpful interaction.”

These interactions may open students’ eyes that there are possible career paths that can lead toward the Justice Department, Posner says. He encourages students to consider starting their career with the Justice Department or other government agencies, places where he and other Law School professors have real connections.

Even without the prestige, improved network, and growth as a teacher, LaCroix said there’s a big benefit to providing expertise to the government. When professors provide their expertise, she says, students see a real-life example of how they can get involved in the government without being a zealot.

“It’s good to show students and the wider public that you don’t have to be a sycophant or a nihilistic critic to get involved,” LaCroix said. “You can roll up your sleeves and get to work, whatever your expertise is.”

Hal Conick is a freelance writer based in Chicago.