'A Struggle That Will Succeed'

How the Law School Community Helped Advance Gay Rights

Throwback Thursday is an occasional feature offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history. This is our fourth installment.

One day in the fall of 1984, a first-year law student walked to the front of the classroom as Professor Geoffrey R. Stone was preparing to teach Civil Procedure I and jotted an announcement in a corner of the chalkboard: “Lesbian and Gay Law Student Group meeting at 5 p.m. in Room C.”

Eric Webber, ’87, who had transferred that year from the UChicago business school, hadn’t asked permission or reserved a room; he didn’t even know if anyone would show. But he had started a similar group at the business school, and he wanted one at the Law School, too. After class, Stone looked intrigued. “I didn’t know we had a Lesbian and Gay Law Student Group,” he said.

“Well,” Webber replied, “we do now.”

And they did: when Webber went to Room C at 5 p.m. — or to whatever room at whatever time; the exact details have faded — seven or eight other men and women joined him for the group’s first meeting. Later that academic year, the Law School formally recognized its first gay student organization.

“It was very significant, and that is best understood in the context of the world as it was 30 years ago — it was a much less welcoming and, frankly, often hostile place to be lesbian or gay,” said Webber, a Los Angeles attorney who in 2011 became the first openly gay President of the Los Angeles County Bar Association. “I thought a visible presence of lesbian and gay students was necessary to start the process of normalizing gay rights. If we all remained in the closet, that was never going to happen. Having a student group made it easier to come out, and it reminded fellow students and the faculty that there were people in the classroom who were lesbian and gay.”

As the nation awaits the Supreme Court’s ruling on same-sex marriage, there has been much attention paid to the evolution of gay rights across the country — the setbacks and the firsts, the constitutional debate, and the swiftly changing tide of public opinion. And the Law School occupies a space in this narrative with its own story, one that is sprinkled with student activism, milestone contributions, and an abiding desire for justice.

When Illinois became the first state to decriminalize consensual sodomy in 1961, it was a Law School professor, Frank Allen, who chaired the committee that revised the code. The Law School hosted the nation’s first law conference on sexual orientation in 1987, and in the mid-1980s, Law School students played a part in pushing the University to include sexual orientation in its non-discrimination policy. Alumnus James C. Hormel, ’58, the Law School’s first full-time dean of students, became America’s first openly gay ambassador in 1999. And ten years before, he was one of several donors who established the Stonewall Scholarship Fund, which is awarded to a Law School student who is likely to use his or her legal education to further gay and lesbian rights; it was the first scholarship of its kind in the nation. In 1992, the University of Chicago became one of the first major universities in the country to offer same-sex domestic partnership benefits for faculty, staff, and students — and a committee chaired by Law School Professor Richard Epstein played a critical role in bringing that about.

“A lot of people (from other parts of the University) felt like their LGBT activism was separate from the higher intellectual ‘life of the mind,’ but the Law School was one of the places where people were able to bring together serious intellectual work and a commitment to social justice and fighting for rights,” said Lauren Stokes, a doctoral candidate in history and co-curator of Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles, an exhibit on the history of LGBTQ life at UChicago that is on display at the Special Collections Research Center Gallery through June 12. Research for the project included 96 oral histories with current and former members of the UChicago community — among them Hormel, Webber, and four other Law School alumni.

“The University of Chicago has been extraordinarily supportive — the Law School in particular,” Hormel told Stokes during his oral history interview in 2013. Hormel, a former US Ambassador to Luxembourg who came out as gay after he left the Law School as Dean of Students and Director of Admissions in 1967, is the author of Fit to Serve: Reflections on a Secret Life, Private Struggle, and Public Battle to Become the First Openly Gay U.S. Ambassador (2011). An active member of the Law School community, Hormel also created the school’s James C. Hormel Public Service Scholarship in 1986 to encourage law students to go into public service. “It’s also been amazing for me to see how the LGBT students have sort of emerged at the Law School. They are really quite a fascinating group. When Geof Stone was dean (between 1987 and 1993), I think he was very encouraging.”

***

Although it was likely not known at the time — or for a long while after — the Law School’s first female graduate, Sophonisba Breckinridge, 1904, was a lesbian. Breckinridge, who became a prominent figure in the University and helped found the School of Social Service Administration, carried on decades-long relationships with two other prominent University of Chicago women, Marion Talbot and Edith Abbott.

Stokes’ research suggests that the University of Chicago, and Illinois in general, was a draw for gay students after 1961 because, until Connecticut decriminalized sodomy ten years later, Illinois was the only state that had legalized private, consensual sodomy between adults. But by most accounts, gay students were largely closeted for many decades. Stone doesn’t remember anyone being openly gay when he was a Law School student between 1968 and 1971; when he returned to teach in 1973, there was one openly gay male student.

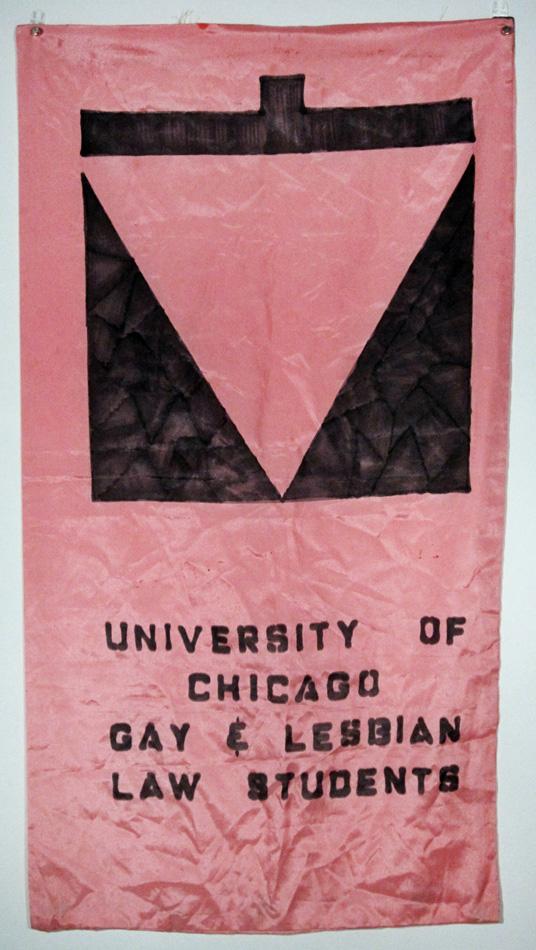

In the 1980s, though, as the AIDS epidemic was reaching crisis levels, things began to change. The new Lesbian and Gay Law Students Group — a name that went through several iterations before taking the name OutLaw around 1999 — formed and became active, pushing to add sexual orientation to non-discrimination policies at the Law School and University-wide. The group had a pink banner that featured a triangle that was designed to also represent the scales of justice. Stokes found it recently, balled up and wrinkled, as she was poring over artifacts in the Gerber-Hart Library, a depository for LGBTQ records and artifacts in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood.

The student group also staged protests. One year in the mid-1980s, during on-campus recruiting, a group of gay and lesbian law students decided to protest the anti-gay hiring practices of both the CIA and the military Judge Advocate General’s Corps. They signed up for every open recruiting interview slot and "played it straight" until the end of the interview, when they revealed that they were gay.

"We wanted not so much to harass the (recruiters),” Webber recalled during the oral history interview, “but to have a thoughtful conversation about how the policy was denying them the interest of very qualified people."

Then, on April 11, 1987, the Law School held the Chicago Conference on Sexual Orientation and the Law, organized by the Lesbian and Gay Law Students group with support from several Law School faculty members. Although Yale had held a conference on AIDS the year before, this was the first national law conference on sexual orientation. Stone, then the dean-designate, offered opening remarks in which he called “the issue of sexual orientation perhaps … the most serious civil rights issue facing our nation today.”

“Just the other day, one of my finest students asked me whether, in light of his sexual orientation and his public involvement in gay and lesbian activities, he should even bother to apply for a judicial clerkship,” Stone told the audience. “That such a question can seriously be asked is itself a tragic statement about our profession and our society. There has, however, been progress. It is progress that has been brought about by those who, like those a generation earlier who refused to return to the back of the bus, have refused to return to the closet. It is a civil rights/civil liberties struggle of the purest sort. It will take wisdom, patience, and courage.

“And it is a struggle that — in the end — will succeed.”

***

Stone remembers the day Webber wrote his message on the board in Civ Pro I more than 30 years ago; he even told the story at an OutLaw celebration during the Law School’s Reunion weekend last month.

"When I think back on how far we've come,” Stone said earlier this month, “I have great admiration for our many students, like Eric Webber, who courageously brought this issue into the light and enabled us to move to a more just world.”

Webber, too, has been surprised by the pace of change. He still remembers the devastation he felt when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a Georgia law criminalizing sodomy in Bowers v. Hardwick. It was 1986, when Webber was a rising 3L working as a summer associate. “It was a kick in the gut,” he said. At the time, it was hard to envision what the next few decades would bring — including his own 2008 marriage in California.

“If you had asked me, as a third-year law student, if I would ever be married to the man I love,” Webber said, “I would have said, ‘Not in my lifetime.’” Today, however, he is happily married to his life partner of almost 33 years, a man Webber met before his days as a 1L writing announcements on the Law School’s chalkboards.

“Thinking back three decades,” Webber said, “the positive changes in laws and attitudes affecting LGBT people truly are extraordinary. The entire Law School community can be proud of the role it played helping to bring that about.”