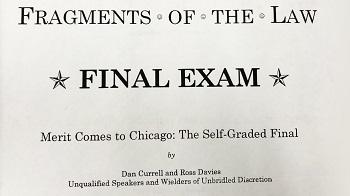

Fragments of the Law

How a 1997 Student Lecture Series Mixed Wit, Wisdom, and the UChicago Way

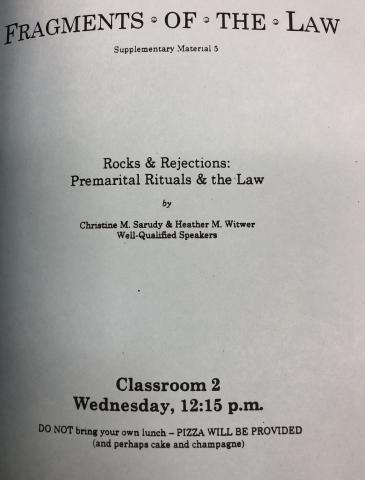

Nearly 21 years ago, during the spring quarter of their third year, a small group of University of Chicago Law School students decided to teach each other a series of lunchtime law classes. One student spoke about presidential powers in Eastern Europe, and another showed clips from Warner Bros., the Dukes of Hazzard, and old Buster Keaton films for a session on the law of the chase. Two women—one married and one engaged, both to classmates—lectured on the laws of broken engagements.

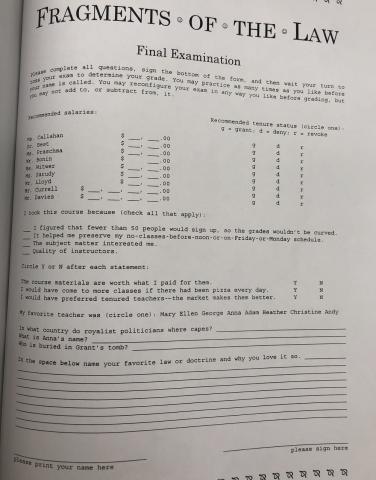

There were syllabi and handouts and vague promises of food, although all these years later it’s hard to say whether the vodka and brown bread, popcorn and candy, or cake and champagne actually materialized. It’s hard to say, even, who first suggested the offbeat project—although most people are fairly sure it was Ross Davies and Dan Currell, both ’97—or whose idea it was to assign final grades by asking each student to toss a single-sheet exam onto the library steps, which were marked with scores of varying respectability.

What the dozen or so participants, mostly members of the Class of 1997, do remember is this: Fragments of the Law was quintessentially UChicago, rich with humor, tightknit collegiality, and the fruits of unbounded curiosity. The legal discussions that unfolded in each class were real, but so was the laughter. And some two decades later, it’s a thread of Law School history that remains lodged in the minds of its participants—albeit in various fragments of detail—as a quirky reminder of an academic culture that taught them the value of expansive, non-judgmental inquiry and the virtue of clever amusement.

“The project was simultaneously really silly and really serious, and like many things, I think it came out of talking in the Green Lounge,” said Davies, who coyly denies leading the charge. “The faculty knew we were doing this. The administration was perfectly fine letting us use a classroom. The Law School is an intellectually entrepreneurial culture, and this is the kind of thing our instructors modeled for us: if you have a good idea, do something with it, and do it well. Do it thoroughly and in a disciplined way. And so this Fragments of the Law thing, yes, it was sort of a silly joke. But at our law school, we do these things right—including the nonsense. And that’s what it was: very highly refined nonsense.”

The unofficial class—no actual credit was given—was intended as "anti-matter" to the first-year jurisprudence class Elements of the Law and is preserved in a hardbound book that Davies made as a memento. The 1.25-inch volume contains reprints of all the handouts, as well as posters advertising each class, beginning with “A Comparison of Presidential Powers in Eastern Europe: Custom-Made Constitutions.” That session was taught by Mary Ellen Callahan, ’97, who before law school had worked at the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress as part of the Special Task Force on the Development of Parliamentary Institutions in Eastern Europe.

“I remember Ross came to me, and he said, ‘I think everyone would benefit from learning from you about Eastern Europe, and by the way, you have to be funny,’” said Callahan, now an assistant general counsel for privacy at the Walt Disney Company and the former chief privacy officer for the US Department of Homeland Security. “And I was like, ‘OK I’m in.’ The project was driven by this pure desire to educate ourselves a little bit more about life and society and to learn from others. It was hilarious, and it was a fun way to end a law school career, to do something smart and funny and frivolous.”

In the back of the volume there’s a copy of the final exam—which includes questions like, “[N]ame your favorite law or doctrine and why you love it so,” and “In what country do royalist politicians where [sic] capes?”—along with the scores used to label the library steps during the final-exam grade toss. (The highest grade, 87, was reserved for Howard C. Nielson, Jr.,’97—now a nominee for federal district judge in Utah—because “it was generally felt that Howard got unearthly high grades,” Currell said). The exam also asked for future salary recommendations for each of the nine instructors—but, curiously, seemed to suggest far higher ceilings for Currell and Davies and an extraordinarily low ceiling for their friend Adam Bonin, ’97.

Davies, now a professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, chuckled when asked about both the exam and the genesis of the project, shuffling responsibility off onto Bonin, whom he called “a mad genius.”

“At most Adam manipulated me into typing that up to fit his vision of what legal education should be,” Davies said. “I was merely an innocent puppet and should not be held accountable for any of this.” (Typical response, Currell said when told of Davies’ denial, adding that “it’s possible that I was involved—it sounds like something I would have done—but the safe bet is that Ross was behind it.”)

Everything about the project—from the eclectic topics to the “self-graded final” to the affectionate and teasing recollections—reflects two things, participants said: the personalities of those involved and the sort of thing that develops when a community is both ideologically diverse and willing to mix it up a bit. The Class of 1997, after all, isn’t alone in its dual devotion to intellectualism and jest—just ask Senator Amy Klobuchar, ’85, and her peers in the “the happy class” or anyone who has ever participated in the Law School Musical.

“One thing I remember strongly to this day is the sense of fun—and it was, of course, a very Chicago thing to consider that our idea of fun,” said Anna Ivey, ’97, who later returned to the Law School as the dean of admissions and is now the CEO of Inline, which makes software that helps people with their college applications. “It really reflects the culture of the Law School and the University at large because it was all built around intellectual curiosity and inquiry. You could apply that curiosity to serious things, and you could apply it to silly things.”

Many of the Fragmenters worked on Law Review—Davies, naturally, was the editor-in-chief—and several participated in the Musical. That year’s show, a send-up of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, featured Oompa-Loompas in bicycle helmets and bright yellow pants—a nod to the yellow slicker pants Davies sometimes wore when he rode his bike to the Law School in inclement weather. Like many of their Law School peers, the Fragments crew was polymathic in their interests and eager to learn and share.

“I didn’t know anyone in my class who was interested in just one thing,” Davies said. “You could sit down to talk about one thing and learn that someone was an expert on some other thing or had some passion that you never knew about. Every conversation was a really good documentary, and you never knew where you were going to end up. It’s one of the things I enjoyed then, and still enjoy, about my classmates.”

Currell—who was originally supposed to teach “Voodoo and the Code Napoleon: An Interdisciplinary Critique of Louisiana Evidence,” with Clegg Ivey, ’97, but says neither has any recollection of having followed through—was particularly known for his appreciation of law’s dustiest nooks and crannies.

“I had taken an eclectic collection of classes—the joke was that I was taking every kind of law that you couldn’t possibly practice,” said Currell, now the managing director of AdvanceLaw, a general counsel advising firm. “My highest grade in law school, I think, was Mesopotamian Law, and, well, that was sort of representative.”

Bonin used his session, “The Social Organization of Law: A Multimedia Approach,” to show favorite video clips—but he also used it as a chance to discuss favorite legal cases. Among his screenings was the 1944 animated short “Russian Rhapsody” from Warner Bros., a seven-minute film that featured Soviet “gremlins from the Kremlin” sabotaging German planes and infuriating Hitler. The clip gave him a loose entrée into discussing United States v. Tiede, a 1979 overseas hijacking case that had been heard in an American court in Berlin. The case, which involved East German defendants, a Polish airliner, and a forced landing in an American-occupied sector of West Berlin, centered on whether the United States could exercise jurisdiction. It was one of Bonin’s all-time favorites from law school.

“The United States and a lot of the European countries had recently signed an anti-hijacking treaty with East Germany, and they wanted to see it enforced,” said Bonin, now a political law attorney in Philadelphia. “And so they created a United States Court for Berlin and put a federal judge there. And the question was, ‘Does the Constitution apply to these proceedings?’ It’s a really thoughtful and defiant opinion in which the federal judge says, ‘As long as I am here, the Constitution travels with me and [the defendants] are entitled to a trial by jury.’”

The Fragment nearly everyone remembers was “Rocks & Rejections: Premarital Rituals & the Law,” taught by Heather M. Witwer, ’97, who had married Rob Witwer, ’96, during law school, and Christine Sarudy (now Roberts), ’97, who was engaged to marry Lyle Roberts, ’96, after law school.

“Heather and I were always together,” said Roberts, now an active volunteer who is home with her children. “Ross asked us if we wanted to teach a class together—and on anything we wanted. There had just been something in the news about a man in New York who felt he had been swindled out of the pre-marital furniture and the engagement ring he had bought … when his girlfriend broke up with him, and he wanted it all back.”

The two were intrigued and wondered how each state’s laws would apply, and eventually ended up looking more broadly at the definitions of marriage and engagement. As they shared their memories of the class during a recent conference call, the two women—still close friends and both still married—laughed as they remembered that period of law school, which was notable for another reason.

As Fragments was unfolding, so was another project—one rooted in a similar set of values. Davies and two other classmates, Montgomery Kosma and David Gossett, both ’97, had decided to resurrect a turn-of-the-20th-century magazine; the result, of course, was The Green Bag: An Entertaining Journal of Law (second series). The magazine is known today for its engaging take on legal issues and its production of bobblehead dolls depicting US Supreme Court justices.

“I think a lot of [Fragments] was driven by Ross’s personality—he came to school with a very expansive view of what the law was in the world, and what fun it could be,” Roberts said. “You can see that in his work with the Green Bag—he has a great sense of perspective tinged with a sense of humor. … On Law Review, there were a lot of big personalities, and it could have been messy. But it wasn’t because Ross was just very down-to-earth, and he approached any issue or problem with, ‘Let’s think about this.’ When you’re that age, a lot of what you do is react, but Ross was thoughtful. It was an invaluable example to cocky, young soon-to-be lawyers.”

Witwer, who now teaches high school, added: “Ross is relentlessly positive. People could be dragging their feet or complaining about something, but Ross was always smiling.”

Ivey says she has never encountered another culture quite like the Law School or people quite like the ones she met there. “I mean, who revives a long-defunct legal journal?” she said of Davies. “He was part of making it such a fun and quirky place to be.”

And that sense of fun, she added, is an important part of the experience.

“What happens inside the classroom, of course, matters—but what happens outside the classroom matters just as much,” she said. “These are some of the things that you carry with you for the rest of your life.”

Throwback is an occasional series offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history.