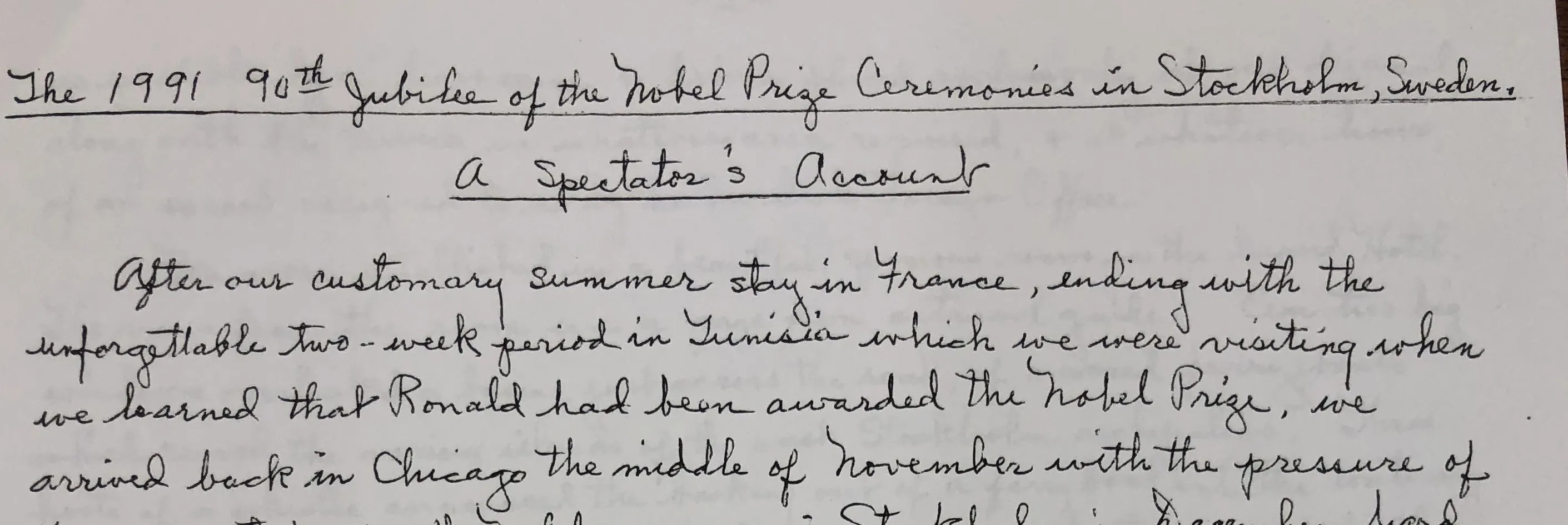

Sophonisba in Love

Throwback Thursday is a regular feature offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history. This is our third installment.

It was the summer of 1928, and Sophonisba Breckinridge was in love. Times two.

The educator and social reformer, who had become the Law School’s first female graduate in 1904, was traveling with one woman and desperately missing another. And both, like Breckinridge, were influential women on the University of Chicago campus: Marion Talbot, who had served as the University’s Dean of Women before retiring in 1925, and Edith Abbott, Dean of the School of Social Services Administration that she and Breckinridge had co-founded.

“I don’t see how I can go on tomorrow,” Breckinridge wrote to Abbott that May as she traveled to Europe with Talbot. “I can think only of how good you are to me, and how I am so foolish and uncertain and disagreeable. I think you understand, though, dear.”

In July, she wrote: “I can hardly bear it any longer. Dear, I love you so.”

The story of what appears to be a decades-long UChicago love triangle — marked by an evocative intertwining of intellectual and personal devotion, a fraught tussle for Breckinridge’s affections, and quiet acknowledgments that stopped short of actually labeling the women lesbians — was recently discovered by University of Montana History Professor Anya Jabour, who has been researching Breckinridge for several years. Jabour, who also co-directs her school’s Women's and Gender Studies program, is writing what will be the first full-length biography of Breckinridge, which will be published by the University of Illinois Press. She recently spoke about her findings at a campus event sponsored by the University of Chicago’s Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality.

“This opened up a whole different side of her,” Jabour explained the next day over coffee at the Law School. “I had been interested in all her professional achievements and all of the obstacles that she encountered. She was so incredibly talented, intelligent, and educated, yet she still struggled to find her niche. To finally see this part of her personal life — it was just so exciting to round out the picture.”

The new Breckinridge details offer glimpses into the University of Chicago’s formative years, the sexual politics of the early 20th century, and the inner workings of the enigmatic pioneer who was part of the Law School’s first graduating class. Known affectionately as “Nisba,” Breckinridge was a strikingly complex figure: a woman of unfailing modesty who grew prickly when she wasn’t taken seriously, a progressive leader who could be seen strolling the campus in Victorian garb well into the 20th century.

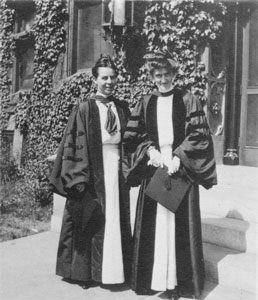

She was barely five feet tall; when she was at the Law School, janitors had to shorten her desks so her feet would touch the ground. But she was powerful and persistent, and she had racked up a litany of University firsts in addition to her JD: she was a founder of the SSA, the first woman to earn a PhD in political science, and the first woman granted a named professorship. In 1905, she also began teaching what was arguably the first women’s studies course in the United States — a class in the University’s Department of Household Administration that focused on the legal and economic status of women.

But despite her boldness, Breckinridge could also be vulnerable, loving, and prone to loneliness. She was a prolific letter writer, composing heartfelt missives to her loves, even when she was busy. “I’ve been hustling a little over students, and degrees, and theses, and so forth,” Breckinridge once wrote to Talbot. “I love you just the same, all the time.” In another letter to Talbot, she pined: “I shall be loving you, and thinking of you, and wishing that I could know just how you are.”

***

Breckinridge loved Talbot first, and they met during a pivotal time in Breckinridge’s life.

Breckinridge loved Talbot first, and they met during a pivotal time in Breckinridge’s life.

Breckinridge had grown up in Kentucky, the daughter of a politically prominent attorney who served in Congress. “But like many women of her generation, she struggled to find an acceptable outlet for her intelligence and her ambition,” said Jabour, a women’s history scholar who came across Breckinridge while researching what she calls her “southern schoolmarm project.”

Breckinridge had attended the University of Kentucky and then Wellesley, returning to her home state to study law after graduation in 1888. She was admitted to the Kentucky bar in 1892 — 10 years before she enrolled at the Law School. Breckinridge declined to pursue a law career because of poor prospects for women lawyers, but — contrary to many writings — she did try at least two cases in the late 19th century, Jabour discovered. One was a custody case in which Breckinridge represented a mother of four who had fled an abusive husband in the middle of a cold winter night. Despite laws that favored the husband, Breckinridge succeeded in having the two youngest children placed with the mother.

“I was floored,” Jabour said. “Most people don’t realize that Breckinridge practiced law.”

During these post-Wellesley years, Breckinridge lost her mother, struggled with depression, and discovered that her beloved father had been having an affair with a much younger woman. But in 1894, she visited a Wellesley classmate in Chicago and met Talbot, who convinced her to pursue graduate work at the University. This move changed the trajectory of Breckinridge’s life: she began studying political science with her mentor, Professor Ernst Freund, who helped found the Law School and encouraged Breckinridge to enroll. She became an integral part of the University fabric and played an important role in social causes throughout Chicago, living for a time in Jane Addams’ Hull House with other social reformers.

Talbot continued to be a key figure in her Chicago life. She hired Breckinridge as her assistant in the Dean of Women’s Office, as well as in the women’s residence halls. The two grew close personally and professionally, sharing adjoining offices, traveling together, and becoming increasingly recognized as an inseparable pair. Talbot, who became Breckinridge’s “tireless advocate” at the University, often accompanied Breckinridge to visit her family in Kentucky. In 1912, Talbot’s parents deeded their family vacation home to both women, and the two continued to visit it together until the 1930s.

But in 1905, a new woman — Abbott — entered the scene. She was a student in Breckinridge’s women’s studies class, and the two grew close, emotionally and professionally — eventually becoming as inseparable as Breckinridge and Talbot had once been. Although Breckinridge and Abbott didn’t live together until the 1940s, they attended events together, shared hotel rooms at conferences, and merged their personal and professional lives. They wrote several books together, co-founded the SSA, and worked together in government agencies and on committees. Students referred to them as “A” and “B,” and became accustomed to seeing them together, utterly absorbed in their conversation and each other, Jabour said.

A Chicago graduate once wrote: “I had seen Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge walking from the Law building to the Gothic turrets of their offices in Cobb Hall. Their preoccupation and leisurely pace gave them a pathway to themselves. Students walked around them on the grass. These diminutive Victorian ladies seemed larger because of their dress. Their skirts swept the sidewalk. Miss Abbott loomed larger in her black hat and dark dress. Miss Breckinridge’s floppy Panama hat and voile dress set off a soft, vivacious face and slender feminine figure.”

Of course, the growing closeness left Talbot feeling uneasy, jealous, and threatened, and she and Abbott became increasingly contentious, even exchanging a series of perturbed letters.

“They appeared to be locked in a battle to prove which of them loved Breckinridge the most,” Jabour said of the letters. “Later events would indicate that (Breckinridge) did indeed have so much room for life and loving and that she could, and did, maintain a close relationship with both Talbot and Abbott for the rest of her life.” Talbot eventually, though reluctantly, accepted her second-place position as Breckinridge’s feelings for Abbott intensified.

In 1933, as Breckinridge was traveling to South America for the seventh Pan-American Conference, she wrote to Abbott: “I feel dreadfully. I have never before been so helpless before space and time. I think of you all the time. I get little sleep, and I long for the sight of you. I am really not fit any more to do things alone. It is so long, and so far.”

About 15 years later, when Breckinridge died — just a few months before Talbot died — it was Abbott who made the funeral arrangements, received the condolences, and was both the executor and primary beneficiary of Breckinridge’s estate.

***

Breckinridge’s close relationships weren’t exactly secrets, though neither were they acknowledged in the way they might be today, Jabour said.

A former student once recalled: “One of my memories is Little Miss Breckinridge trudging along over a few blocks to see Miss Talbot. She went every night to see her. On the other hand, Miss Talbot and Miss Abbott were not friends. I don’t know what the cause was, but at any rate, Miss Breckinridge loved both of them.”

During the interwar era, Abbott and Breckinridge were part of a unique subculture in which about a third of women holding key government positions “eschewed heterosexual marriage in favor of relationships with other women,” Jabour said. “These female politicos frequently mixed inquiries about one another’s partners with strategizing about political initiatives.” When Breckinridge died in 1948, it was members of this group that flooded Abbott with messages of condolences, Jabour said, which effectively acknowledged – and possibly named – the significance of the same-sex relationship.

Still, for the most part, Breckinridge escaped mainstream scrutiny and appears never to have identified outwardly as a lesbian, Jabour said.

“People weren’t using the language of homosexuality and lesbianism when she was growing up, and these words were not in common parlance until the 1920s. So, until she was in her 60s, that just wasn’t even a category,” Jabour said, adding that well-to-do women were particularly unlikely to acknowledge their homosexuality — even if the intensity of their same-sex relationships was obvious to those around them.

“They just didn’t talk about it. People went on and on about their relationships, but didn’t connect the dots,” Jabour said. “By the ‘40s, there was a lot of popular concern about homosexuality, but by then, Breckinridge was in her 70s. So I think it didn’t occur to people to draw a link between these respectable women in their hats and their skirts and the young, working-class lesbians who went to actual lesbian bars and dressed either ‘butch’ or ‘femme.’ That was a totally different subculture.”