Let’s Make a Deal, Good Sir

The Hiring of the Law School’s First Faculty

Throwback Thursday is a monthly feature offering glimpses into the Law School’s rich history. This is our first installment.

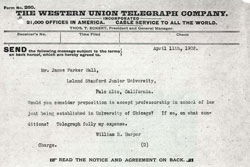

The story of the Law School’s birth—or snippets of it, anyway—lives in a small stack of 112-year-old correspondence exchanged between the University of Chicago’s first president, William Rainey Harper, and the elite scholars he was recruiting as faculty. Their voices, at once gracious and demanding, echo in the crisp telegrams and mannerly letters that outline their expectations.

“My dear sir,” the missives often begin, before laying forth an employment proposal or thoughts on the curriculum. They generally conclude with a flourish of gentility: “Assuring you of my hearty co-operation, I am very truly yours,” or “With highest esteem, believe me.” Some of the letters are typed, lightly drawn with the occasional edit, and others dress their pronouncements—It strikes me that it would not be best to reproduce the Harvard Law School here—in gracefully curved handwriting. Together, the writings tell of shrewd negotiation, high expectations, and an unflagging devotion to excellence.

Handwritten Western Union draft, April 1902: Professor J.P. Hall, Leland Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. — Telegram received. School opens Oct. first. Beale of Harvard Dean. Methods and spirit like Harvard. Beale suggests you take Commercial Law and Evidence or Equity. Full professorship salary fifty-five hundred dollars. We know Harvard offer. Have written. Other colleagues Mechem of Michigan probably Mack and Lee with others. William R. Harper.

In April of 1902, there were less than six months before the University of Chicago Law School was due to open. Joseph Henry Beale, Jr., had just agreed to serve as founding dean during a leave of absence from Harvard, but only after substantial wrangling over how closely the curriculum would resemble Harvard’s. Now Harper was busy hiring faculty. Ernst Freund was transferring to the Law School from Chicago’s political science department, and Harper had stolen Julian W. Mack and Blewett Lee from Northwestern University. He was working to hire Floyd R. Mechem from the University of Michigan, as well as James Parker Hall and Clarke Butler Whittier from Stanford.

closely the curriculum would resemble Harvard’s. Now Harper was busy hiring faculty. Ernst Freund was transferring to the Law School from Chicago’s political science department, and Harper had stolen Julian W. Mack and Blewett Lee from Northwestern University. He was working to hire Floyd R. Mechem from the University of Michigan, as well as James Parker Hall and Clarke Butler Whittier from Stanford.

The urgency was palpable.

The Western Union Telegraph Company, April 28, 1902: Professor Clarke Butler Whittier, Leland Standford (sic) University, Palo Alto, Calif.—Would you consider proposition of professorship in new faculty of Law. Salary fifty-five hundred. Answer. Beale very anxious. William R. Harper.

The salary was generous, among the highest of any American law school; it was a strategy the business-savvy Harper used to lure prominent scholars to departments throughout the university. It was more than double what Harvard had offered Hall for an assistant professorship, and Harper hoped it would be high enough to lure Mechem, too.

Excerpt of typed letter to Harper from Mechem, April 3, 1902: I am led to say there are conditions upon which I should be willing to consider a proposition to remove to Chicago …

Mechem wanted to be in charge of constitutional law, taxation, and the law of public officers and offices, and he wanted to be sure he had a “reasonable amount of leisure for research and writing.” His third condition involved money:

Mechem wanted to be in charge of constitutional law, taxation, and the law of public officers and offices, and he wanted to be sure he had a “reasonable amount of leisure for research and writing.” His third condition involved money:

I should expect that my salary shall be of the highest class paid to professors in the School of Law. I am not mercenary, but I am jealous of that sort of professional standing which comparative salaries usually indicate.

I am entirely satisfied with my position here, and am in no sense anxious to change. The authorities and people here have been exceedingly generous to me, and I find that offers of further kindness are likely to increase the difficulties of decision to leave …

Some back and forth ensued as Mechem weighed his obligations to Michigan. Harper persisted, at one point writing, “We want you, and we want you very much.” Mechem eventually agreed to come to Chicago, but not in the first year.

Harper was more immediately successful with Whittier, who accepted quickly, and with Hall, who first considered the offer from Harvard.

Typed letter to Hall from Harper, April 16, 1902: We understand that Mr. Eliot sent you the same evening the proposition to accept an assistant professorship at Harvard. We are hoping you may see your way clear to join us in Chicago and help establish a new school which shall … do for the west what Harvard has done for the east. The faculty is a most excellent one as thus far constituted …

Five days later, Hall accepted.

Handwritten letter to Harper from Hall, April 21, 1902: Let me thank you for the offer, which to a man of my age seems particularly generous and attractive. … I shall enjoy working with (the faculty) in organizing the school and getting it underway.

Typed letter to Hall from Harper, April 29, 1902: I wish to express my great appreciation of your prompt reply, and to assure you that we shall look forward with great satisfaction to your coming. You will be glad to know that arrangements were completed yesterday for the money which will enable us to build a new law building, and we shall begin work as soon as the faculty has agreed upon plans.

Looking forward to the pleasure of seeing you October first next, if not earlier, I remain yours very truly, W.R. Harper.

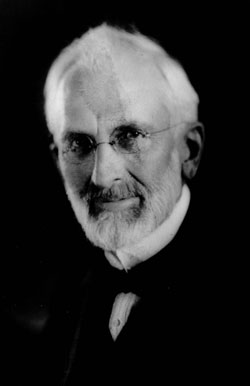

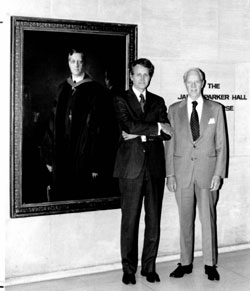

On May 1, 1902, the university’s trustees approved the Law School’s first faculty. Hall went on to become the Law School’s first permanent dean, and the longest serving, holding the position from 1904 to 1928. His son, J. Parker Hall II, served as University Treasurer from 1946 to 1969, and his grandson, J. Parker Hall III, was a longtime University Trustee beginning in 1988.

the Law School’s first permanent dean, and the longest serving, holding the position from 1904 to 1928. His son, J. Parker Hall II, served as University Treasurer from 1946 to 1969, and his grandson, J. Parker Hall III, was a longtime University Trustee beginning in 1988.

Mack taught at the Law School until his retirement in 1940. He also served as a federal appellate judge beginning in 1910, serving in the Seventh, Sixth, and Second circuits. Before that, he was a judge in Cook County Circuit Court and in the First Illinois District Appeals Court, and helped found Chicago’s first juvenile court.

Freund taught at the Law School until 1932 and was a leader in the development of administrative law in the United States in the early twentieth century.

Mechem taught at the Law School until his death in December 1928. Shortly after, the school’s third dean, Harry A. Bigelow, wrote in the American Bar Association Journal: “During the course of his long career as a teacher of law, he came in contact with thousands of students. It is doubtful if any member of the teaching profession ever had a greater and more enduring hold upon the affections of those with whom he so came in contact than did Mr. Mechem.”