Fifty Years of Clinical Legal Education at Chicago Law

“The answer to the question of how should a Clinic operate—to be of optimum value to students and clients—can be found by an alert, resourceful law school. I believe the answers will come only after some careful study and experimentation by a law school of national reputations. The Law School of the University of Chicago should be that institution.” — Junius Allison, Associate Director of the National Legal Aid Association, in a 1956 letter to the University.

The goals of the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic have long been to help those who need assistance and to teach students the practical ins and outs of legal practice at the same time. Over the past half century, the methods and models used to achieve these goals have changed, but the desire to instill in students an understanding of the value and need for public-assistance law never wavered.

Since its inception, the Mandel Clinic has been regarded as a superlative example of what a law school–affiliated legal aid clinic should be. With dedicated teachers and bright, eager students, literally hundreds of thousands of people have been helped directly by Clinic staff. And many, many more have benefited from the lawsuits and advocacy work the Clinic has performed.

The Clinic has influenced attorneys who have gone on to start other legal aid clinics at schools across the country, from Vanderbilt University Law School in Tennessee to the Boalt Hall School of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. Further, its reach is more than national, as several law schools outside of the country have studied the Mandel model when creating their clinics.

At its inception, when it opened with two attorneys and one secretary, its creators firmly believed that the Clinic would help people well into the twenty-first century. Today, with its expanded staff, its comfortable offices, and its mass of hardworking students, the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic continues to be a credit to its founders.

1950s

By the time the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic opened, Dean Edward H. Levi had spent six years writing hundreds of pages worth of memos, letters, and proposals in an attempt to bring his plan for a legal clinic at the Law School to fruition. In a 1951 memo, he wrote:

“Such a legal clinic would be a major step in American legal education. It would put the law schools in a position where they would be dealing with the facts of actual cases . . . . It would be an experiment in the training of lawyers using techniques analogous to those employed in medical schools.”

Levi’s vision was clear, but the route to success was not as apparent. Over the next few years, a number of proposals were considered and discarded, including one put forth by the National Legal Aid Association for a Legal Center in Chicago that would include students from six area law schools.

However, in 1956 a solution to clinic formation was found in the form of philanthropist Edwin F. Mandel, whose family had funded the development of several medical clinics at medical schools. As Levi noted in his funding proposal for Mandel, “The concepts of clinical service that have proved so successful in medicine are applicable to the practice of law. As with medical clinics, legal aid clinics can provide a very high quality of free services for low-income families. Such clinics are also important in providing essential facilities for training and research.”

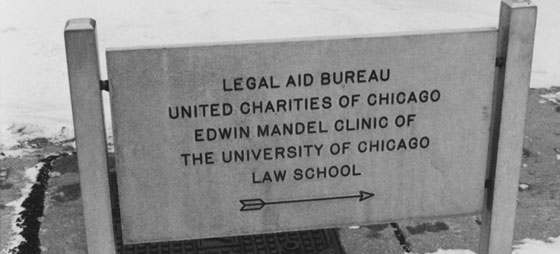

By January 1957, the Law School had a pledge for $75,000 from Mr. Mandel, and a comment that he “would not object” to the clinic being named the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. $25,000 of the Mandel donation was used for equipping the Clinic, and the remaining $50,000 was given over a ten-year period and used for staff and building expenses. The rest of the budget was to be met by the Legal Aid Bureau of United Charities of Chicago, which provided the clinic with two attorneys and a secretary.

Temporarily housed at 1230 63rd Street while it awaited space in the new Law School building, the Clinic was essentially a branch office of the Legal Aid Clinic. Henry Kaganiec, a Legal Aid Bureau staff attorney, was appointed director of the Clinic, and Victor I. Smedstead, Esq., was also brought in. By the time the doors opened on October 1, 1957, hundreds of neighborhood clients were already waiting to receive services.

As many as forty students worked in the Clinic’s first year on a purely volunteer basis. Kaganiec and Smedstead handled all of the cases, all of which were civil in nature as the Bureau was not permitted to take on criminal cases. The lawyers were not appointed to be teachers, and as a result, the students did not take any related classes or receive credit for their work, but simply spent time helping with brief writing and interviewing when they had time to spend in the Clinic.

At the time of the Clinic’s formation, Chicago attorney Alex Elson, ’28, was asked to spend the year studying the Clinic and to write a report of his findings. In the spring of 1958, he suggested several changes to Clinic operations. First, he found it problematic that some clients were being interviewed by students—and not by licensed attorneys— without their knowledge. Elson was also concerned that students did not have proper professional skills to make the interviewing useful. He also felt that the Clinic was not sufficiently associated with the Law School. However, he reported, the students working in the clinic were, “enthusiastic about their experience. They believe they are rendering a service to people in need and tend to place a greater value on the service aspect than any resulting educational benefit.”

Thus changes began. The supervising Law School faculty worked with Kaganiec to make sure that no clients were discharged from the Clinic until one of the attorneys had been consulted. The attorneys and students spent more time discussing methods and cases. Discussion began about appointing a faculty attorney as director of the Clinic and the need for more clerical assistance.

In school year 1959–1960, the Clinic saw 3,185 new and 862 returning clients. Cases were classified in thirty-four categories. Husband & Wife was the largest with 777 cases, followed at a significant distance by Installment Contracts, Wage Assignments & Garnishments, and Recovery of Personal Property.

1960s

Concern about students’ roles at the Clinic swung quite far in the other direction by the early 1960s, according to Stephen Wizner, ’63, who worked there for three years.

“I don’t recall ever interviewing a client on my own, but I did sit in on some client meetings and take notes,” Wizner says. “We were really just being used as paralegals—we had no real instruction other than ‘here is how you do this’ or ‘here is how you do that’ when something needed doing.”

Wizner and the handful of students working with him at the Clinic in the early 1960s worked two to three hours a week in a dark, windowless basement office at the Law School. Clients walked in off the street or were sent from the downtown Legal Aid Bureau office and cases continued to be civil, covering mostly domestic issues, housing, and wage disputes.

“Working with Henry was a lot like being in the Law School itself,” Wizner explains. “He was abusive just like the professors were—if you wrote a motion he would tell you that you were not totally incompetent, which made you feel great. Henry had a total dedication to his clients, he spent a lot of time talking about client-centered lawyering and he really meant it. If we made a mistake he would make it clear that these clients deserve better.”

In the 1962–1963 school year, the Clinic handled 3,479 new cases, along with eighty-two that were pending from the previous year.

By the time Tom Stillman, ’68, reached the Clinic in 1966, students were again meeting with clients alone, but were consulting on all cases with the Clinic attorneys.

“Henry ran the Clinic and pretty much anyone who wanted to work there did,” Stillman recalls. “There didn’t seem to be a huge university connection at that point—he ran it the way he wanted to and he helped a lot of people. We were working on a lot of low-level service stuff—evictions, some civil lawsuits, some prisoner stuff.”

By 1966 Arthur K. Young, director of the Legal Aid Bureau, was eager to have students begin working on appeals. Finding appropriate cases for student learning was a challenge, because such cases normally went through the downtown Legal Aid Bureau office. Further, the three lawyers then working in the Clinic did not have the time to supervise students as they worked through an appeals case. Ultimately, the Bureau and the Law School worked together to create the Appellate and Test Case Program, which generated a large pool of challenging legal research problems for the students.

“The appellate division litigation was considered very sexy stuff,” Stillman, who returned to the Clinic as an Instructor in 1970, admits. “It was fun, and to me, a lot more interesting than landlord-tenant stuff. I mean, this was the beginning of class action and the movement for big change through litigation.”

In March 1967, students addressed a letter to the Clinic attorneys, in which they asked to be assigned to new duties through the Bureau as their work with what was known as the Neighborhood Clinics was dwindling. Interest in legal aid had grown during the 1960s, and the Bureau now faced enough competition that there were no longer even enough cases to keep their attorneys busy, much less a cadre of student lawyers.

By the fall of 1967, the Clinic had three attorneys, two secretaries, and more than seventy students participating in six specialized programs, which were designed as opportunities to have students handle every phase of a legal problem. In addition to the Test Case program, there was a Community Organization Program, a Civil Practice Internship Program and students were also participating in the Federal Defender Program, in which students from the city’s six law schools worked as assistants to a panel of attorneys who worked with all the indigent cases brought into the Seventh Circuit.

Additionally, the educational component of the Clinic was expanding. A series of monthly seminars was scheduled with the Law School, and tours of Cook County Jail and Chicago police patrol car rides were continued. Clearly, the scope of the Clinic’s activities was broadening, and the roles of students were growing. But two major developments would soon alter the character of the Clinic itself and the role that students played there.

First, student interest in participating in the Clinic began to increase dramatically beginning in 1967 as a result of the social revolution that was taking place in cities throughout the country. Civil rights litigation was beginning in earnest, and students and faculty alike saw that the Clinic could become a major actor in the facilitation of change.

Second, in 1969 the Illinois Supreme Court accepted Rule 711, which allows senior law students to appear in court, providing for a far more complete clinical experience than had previously been possible.

“Which was very handy when the riots following Dr. King’s murder took place,” notes Philip H. Ginsberg, who was brought in as director of the Clinic when Henry Kaganiec left in March 1968. “Six weeks after I got to the Clinic, the city was on fire. Everybody, including the public defenders, had left the municipal court building, so my students and I went down there and represented hundreds of people who were really being held without just cause.”

Along with Clinic students, other representatives of the Bureau, including Arthur Young, worked to free defendants, while graduate students from the School of Social Service Administration assisted in persuading the legal community in the city to express its concern for the maintenance of due process.

“Some students were actually winning an argument that persons were being held without probable cause in front of Supreme Court Justice Walter Schaeffer,” Ginsberg explains. “But then he turned his head and looked out the window and saw the flames and that was that.”

All in all, more than two thousand people had been arrested when the Chicago Bar Association initiated a series of conferences with Chief Justice John S. Boyle of the circuit court and other officials.

The times they were a-changing, and Ginsberg, as the first director to be hired and paid for by both the Bureau and the Law School, wanted the Clinic to change with it. He helped to improve the Law School’s relationship with the community around it by establishing an advisory board from two Woodlawn neighborhood organizations, which he felt would help the Clinic to provide better legal assistance to those who needed it.

But he also wanted the Clinic to become more about educating young lawyers. The clinic program for students was formalized into a two-year program for second- and third-year students during the 1968–1969 school year. For the first time, students worked in the Clinic for the summer term while five Social Service Administration students were assigned to it as well. And new volunteers received a formal orientation along with a 200-page procedural manual. True, a few of the previous year’s programs, including the Federal Defender Program, had ultimately failed because, according to a 1969 student report on the clinic, of a lack of sustained central direction from the Law School.

By the end of the decade, the Clinic’s metamorphosis into a first-class learning experience was underway. Already handling more cases than any other law school–affiliated clinic, it now had fifty-five students who handled more than one thousand cases in the 1968–1969 school year. Nearly three hundred divorces were filed, nearly 100 contracts were written, and sixty misdemeanor charges were handled.

1970s

As the 1970s began, the attorneys working for the Clinic were still not recognized as faculty of the Law School, or even simply as teachers. Ginsberg held the grace title of Assistant Professor, but he had none of the benefits associated with that position and he had little contact with the Law School faculty. There were now seven attorneys in the Clinic, and much of the funding was still coming from the Bureau.

Interest in the Clinic was rising, more students were participating, and the need to integrate it more fully into the Law School was becoming more evident.

Consequently, when Ginsberg left for a position in Seattle, Gary Palm, ’67, was brought in as director in March 1970 with the goal of creating more individualized and personal legal training for the students involved.

“Gary came in with a commitment from the Law School to create a more formalized teaching model,” Stillman, who returned to the Clinic in 1970 as a Clinic attorney, explains. “When I got back to the Clinic as a teacher, things had changed. Students were interviewing clients on their own, discussing the cases with the attorneys, and then they would both go to court. It was no longer that the case belonged to the lawyer and you were there to help out. It was more like the case belonged to the students and the attorneys were there to help out.”

Students were required to spend five hours a week on Clinic work, but a 1972 report on the Clinic shows that most students were actually spending fifteen to twenty hours a week on their cases.

“The Clinic saved my Law School career,” says John Kimpel, ’74, whose legal education was interrupted by a tour in Vietnam. “When I came back, everyone I knew had graduated, there was no draft anymore and the students seemed disaffected and didn’t seem to care. I nearly dropped out. But then I found myself in the Clinic doing all this amazing discrimination work—even taking on a case involving the Miami Police Department—and it made the whole experience worthwhile.”

The roles of the attorneys were changing. Each attorney now pursued a specialized area of interest, and his students took on cases in that area. Stillman specialized in employment issues, while others specialized in housing, consumer affairs, housing welfare, and juvenile justice.

“Cases were getting bigger,” Stillman notes. “We even started having cases with recovery and attorney’s fees, which annoyed some of the Law School faculty who thought the Clinic should just be a charitable institution. We won a case called May v. Cook County Hospital, in which men and women in janitorial positions were being paid at different rates. We were working to equalize the wages and pick up some back wages, and we ended up settling. It was one of the first, if not the first, class action that the Clinic handled, because we were representing two or three hundred women.”

Some clients were still being referred by the Legal Aid Bureau, but the two Woodlawn relationships that Ginsberg had created—with the Woodlawn Organization and the Mandel Clinic Advisory Board, which was chosen by the Woodlawn Organization—were providing 70 percent of the Clinic’s clients. The Clinic represented only clients whose incomes were not sufficient to provide even minimal funds for the hiring of legal counsel. Most of these cases were still related to consumer and family issues, but now 16 percent of the Clinic’s cases were criminal in nature.

Frank Bloch, who is now a clinical law professor at Vanderbilt University Law School, came to the Clinic in 1974 and became the public benefits specialist.

“We went from year-to-year on contracts as faculty professors for the Clinic, so we had titles at this point, but no job security,” Bloch says. “But I came to the Clinic specifically to work with Gary Palm—at the time he was a major force in clinic legal education and he was getting a really big reputation for the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. It was a training ground for other clinics. He was creating a coherent approach to legal education—not just direct client representation, but also an emphasis—a nearly religious adherence—to the notion that faculty is co-counsel—that we work collaboratively with the students because experiential learning is so powerful.”

Students at the Clinic were now required to take a trial practice seminar given by Palm and other Clinic attorneys, and received credit for doing so. And some of the work that the Clinic was taking on was changing. Federal lawsuits in several areas were filed, and more cases and research were being directed at law reform.

“We really encouraged that,” Bloch says. “We wanted the learning experience to go way beyond just handling cases to seeing how creative and collective action on behalf of clients can empower clients and make a difference to a wider community.”

The Woodlawn relationships continued to provide the school with clients, and in 1976 students were assigned off-campus to the Woodlawn Community Defender Office. However, funding for the Clinic was a continuing challenge. In 1977, United Charities, the parent organization of the Legal Aid Bureau, cut their budgetary contribution from $170,000 to $67,800. For the 1976–1977 academic year, the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic budget was approximately $270,000. The Law School provided the other $100,000. After much consideration, the Law School determined that funding for four faculty-titled teachers should be created for the Clinic.

Consequently, the Clinic retrenched. The attorney staff, including the director, was reduced to four and the Woodlawn office remained open. Palm’s salary was transferred entirely to the Law School budget, which was deemed appropriate as he was teaching the two-quarter trial practice seminar and a civil rights seminar. Also, because of the reduction of staff, fewer students (about forty) would be able to take part in the Clinic. As a result, the lottery system—which is still used today to select students for Clinic participation—was created as a form of rationing.

Yet even with these reductions, space at the Clinic was still an enormous issue. “The offices in the Law School basement were really closets,” Kimpel says. “When I went into Tom Stillman’s office and closed the door to discuss a case—let’s just say it was very personal.”

Mark Heyrman, ’77, was one of the first teachers to be hired under the newly restructured Clinic in 1978. “I was fortunate that my office mate was in court a lot, because I got to use the chair,” Heyrman explains. “Otherwise, I had to stand.”

Despite the lack of space, new projects were proposed that would expand the reach of Clinic services. Palm and Charlotte Schuerman, then a Project Director at the Clinic, recognized that there was an increasing imbalance between the need for mental health services and the resources to meet those needs. They created an interdisciplinary project between the School of Social Service Administration (SSA) and the Clinic that would allow SSA students to work closely with law students on the mental health cases the Clinic took on to provide more access to services for those clients that needed them. Further, it would give future social workers a much better understanding of the ins and outs of the legal system as they pertain to clients and their needs. Palm hired Heyrman to run this project.

In 1977, Randolph Stone began a three-year stint in the Clinic as a fellow and as a staff attorney with the Woodlawn Organization. And in 1977, Randall Schmidt, ’79, entered the clinic as a student. What began as short-term assignments for each of these men would ultimately evolve into careers that would help shape the future of the Clinic itself.

1980s

Unsurprisingly, with the changes in the United Charities funding for the Clinic, money was to be a major issue for the Clinic throughout the decade. Palm and the other attorneys spent countless hours researching funding sources and filling out applications for grants, and their efforts paid off. In 1982, for example, the Clinic received $220,000 in Council on Legal Education for Professional Responsibility (CLEPR) funds, while federal funds and grants from various law firms and other private donations provided larger and larger portions of the Clinic’s budget. By 1988, United Charities was providing only 18 percent of the Clinic’s budget, while 15 percent came from a variety of grants and from attorney’s fees earned in some of the cases students and faculty took on. Sixty-five percent of the budget came from the Law School and its alumni.

The Mental Health Project was founded with a three-year grant provided by the National Institutes of Mental Health. After the grant ran out, continuing the project would cost $153,000, increasing the Clinic’s budgetary needs. In 1982 fund-raising letters, Dean Gerhard Casper explained that funds were being raised from various interested foundations and that the SSA was also underwriting and evaluating the program.

The program was a success, not only for the clients, but for the students and the Clinic as well. Because of the additional cases the program created, more students were hired at the Clinic—although space became an even bigger challenge.

Other issues that arose as the Clinic passed its first twenty-five years were the status of the Clinic’s teachers and the need to provide more Law School credit for students. In a 1981 memo that Palm addressed to the dean, he wrote that: “We must have improved status, pay and working conditions. For example, non-tenure track, three-to-five year rolling contracts with two years notice of termination, and titles of Clinical Instructors, Assistant Clinical Professors, Associate Clinical Professors and Clinical Professors.” In 1988, Senior Clinical Lecturers received three-year terms.

“I spent ten years on year-to-year contracts, wondering if I would have a job the next year,” Heyrman explains. “Now we are on five-year contracts. It’s a big improvement.”

Palm also wanted the credit possibly earned by students for work in the Clinic to be raised to eight credit hours from four. He also wrote, in a memo to Dean Casper, that he thought the words “Legal Aid” should be removed from the Clinic name, as it would symbolize the shift in emphasis away from an exclusively indigent practice to one with educational goals.

Bigger cases and more universal issues were becoming more commonplace at the Clinic. In 1982, Palm and several of his students won Logan v. Zimmerman Brush, which was decided by the United States Supreme Court. A fair employment practices case, the ultimate decision was of benefit to more than 2,500 people who had filed charges of employment discrimination in Illinois. In fact, as a result of Logan, all of those cases were either settled with a cash payment or reopened.

“The Fair Employment Practices Commission had become very backlogged,” explains Randy Schmidt, who had returned to the Clinic in 1981 as a teacher. “They couldn’t resolve complaints as quickly as they should have, which was supposed to be in 180 days. Twice, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that cases that were not heard in that period had to be dismissed. So in Logan v. Zimmerman Brush, Logan lost not because his claim was invalid, but because of inaction by the commission.”

The Supreme Court ruled that complainants had a property right in their discrimination claims and that those claims had to be resolved in a manner consistent with due process. Dismissing a complainant’s case because of inaction by the agency did not align with due process.

Ultimately, Logan and the passage of the Human Rights Act in 1979 created a slew of new cases for the Clinic, as students did more and more work on employment discrimination cases of every kind—including sexual harassment, religion, race, sex, and age.

“There weren’t a lot of lawyers willing to take these cases so in addition to taking them we also went down to Springfield to work on procedural changes related to these,” Schmidt explains. “In 1984, Gary and I decided to rethink the employment situation and we decided to create a project focused more on individual cases and also on reforming the system.”

That decision also changed the focus of the Clinic itself. Along with Heyrman’s mental health project, the students and faculty of the Clinic were branching out beyond criminal and civil litigation into advocacy.

“When I was a student we were all being trained as generalists,” Schmidt says. “But beginning with Mark’s mental health project we started to find strategies to change the bigger picture. It became much more a focus all the way through the 80s.”

Charles Weisselberg, ’82, who went on to become a clinical teacher at the Boalt Hall School of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, worked at the Clinic as a student and then returned as a teacher for the 1984–1985 academic year.

“When I was a student I worked on a class action lawsuit with Mark, representing people who were defined as sexually dangerous,” Weisselberg explains. “In Illinois, there was a statute that allowed people to be detained without clear and convincing evidence. We challenged the procedure as to how people were evaluated and how they were held. It was a significant piece of legislation.”

By the late 1980s, 30 percent of the Law School’s students were working in the Clinic. They were concentrating on research, legal writing, drafting, interviewing, counseling, negotiation, informal advocacy, and preparation of briefs and were working as trial assistants. In the spring quarter of their 2L years, they were enrolled in the Litigation Methods course, which extended over four quarters and carried six hours of academic credit—the same amount students earn by doing Clinic work today.

1990s

The Mandel Legal Aid Clinic continued to evolve as it entered the last decade of the twentieth century. In 1991, Gary Palm stepped down as director, although he continued on as a clinical teacher, and former fellow Randolph Stone took over the leadership of the Clinic. With his experience as a public defender in both Chicago and the District of Columbia, Stone was an ideal attorney to take the Law School’s clinical legal education into the next century.

The work of the clinical teachers was evolving, and most at this point had gone from simply working in a specialized field to running full-fledged legal projects. Stone arrived with the intention of creating the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project, still extant today, which provides quality legal representation to juveniles accused of crimes. This type of work was not entirely new to the Clinic, as the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic had worked in various capacities at Cook County Juvenile Court since the 1970s. But the project created a constant and more concentrated effort by the Clinic to protect the rights of juveniles at a time when there was a growing interest in trying older juveniles accused of violent crimes as adults.

“Our focus since 1991 has been on the issue of children being transferred from juvenile to adult courts,” Stone explains. “Some of the scientists in the early years came up with ‘super predator’ theory (the idea that a fixed percentage of children are natural-born killers), and we felt that we needed to do something about it. Some forty-five states began to make it easier to move kids into adult court, by lowering ages and expanding categories.”

In 1993, Herschella Conyers was hired by the Clinic to help develop the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project along with Stone, bringing with her a solid background as an assistant public defender, supervisor, and deputy chief in the Cook County Public Defender Office.

Other projects active in the early 1990s included Gary Palm’s Welfare and Child Support Project, which focused on Illinois’ mandatory job search and work requirements for public aid recipients. The child support component of the project provided legal services to indigent children and custodial parents who sought effective child support enforcement from Illinois and Cook County. Schmidt’s Employment Discrimination Project and Heyrman’s Mental Health Project continued their work as well.

Also funded at the time was the Homeless Assistance Project, which provided legal assistance to the homeless and to those who were impaired due to mental illness. The project represented clients in matters involving government benefits, housing, and psychiatric treatment. The project was staffed by both Law and SSA students.

Another major change that came to the Clinic in these years was the introduction of the MacArthur Justice Center. The Justice Center is a public interest law firm whose mission is to litigate civil rights issues that are of significance in the criminal justice system. Invited into the Clinic for a one-year period in 1993, by 1994 they had begun a formal affiliation with the Clinic that lasted until their relocation to Northwestern University in 2006.

“The emphasis on the students handling the cases and learning as many different aspects of a case just continued to grow,” notes Heyrman. “By then we were looking at cases the way we look at them now, before we took them, by three criteria: Does the work required on the case make sense pedagogically? Does the work meet an unmet legal need in Chicago? And finally, what opportunities does the case have to impact litigation or law reform work?”

While the MacArthur Justice Center focused exclusively on litigation work, the Clinic continued to work in advocacy in addition to civil and criminal litigation.

However, by the middle of the decade, funding for the Clinic again became a problem. CLEPR funding to the Law School ended in the early 1980s. Money had been coming from the Department of Education (DOE), which in the late 1980s began giving the Clinic small grants that eventually increased to $100,000 three-year grants. Like the Ford Foundation CLEPR grants before them, the DOE grants were tied to law schools’ commitments to creating and maintaining clinics.

“The last Department of Education grant was for the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Project,” Schmidt notes. “They were, for a while, the Clinic’s largest source of funding. But then, we had to start getting creative.”

According to a speech Randolph Stone made to alumni in 1999, in addition to the loss of DOE funds, the Legal Services Corporation, a federal agency that funds and monitors free civil legal aid in the United States, had its budget cut and had to reduce its contribution to the Clinic. As a result, the Clinic was down to four clinical teachers with faculty titles—Palm, Schmidt, Heyrman, and Stone—when only three years before there had been funding for seven.

Throughout the 1990s, approximately 100 students would express interest in the Clinic every year, while between forty and fifty students were accepted. Given the budget and faculty cuts, fewer than thirty were accepted for the 1999–2000 academic year.

However, it was not all doom and gloom for the Clinic. No longer would students and faculty work in crowded, dark rooms with no room for the storage of files and reference materials. In the fall of 1996, Esther and Arthur Kane,’39, contributed a naming gift to build the Arthur Kane Center for Clinical Legal Education—a 10,000-square-foot structure with offices and conference and meeting spaces as well as a library for the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. The new offices opened on October 11, 1998.

“The new offices were, and are, spacious and we have windows!” Heyrman exclaims. “I mean, my students actually have offices to work in, with desks and chairs. It was an enormous change and it was a wonderful, long-needed change.”

And more positive changes were awaiting the Clinic in the new millennium.

Twenty-first Century

Comfortably ensconced in their new offices, the teachers and students of the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic have been fortunate to receive additional funding for their work from the Law School and other sources since the 2000–2001 academic year. Consequently, the reach of the work the Clinic does has expanded, and more students are now able to participate. Further, the creation of more projects, each of which receives special funding and grants related to its work, has offered students an even greater variety of experience from which to choose.

After the Institute for Justice Clinic on Entrepreneurship opened in 1998, other exciting programs were started at the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. In 2000, Craig Futterman came to the Clinic to start the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project, the first of its kind in the nation. The project has three components—litigation, policy, and community. The students and faculty represent victims of police abuse in both criminal and civil cases at the federal and state level. The project works with both individuals and groups for class action suits in and around policy issues.

“We do a lot of public advocacy,” explains Futterman. “We participate in community meetings, so that our project is more than just some legal scholars and students discussing problems for other people. Instead, at meetings and forums we can work with problems defined by the people involved. And then we can all work together to create strategies for working with and negotiating with officials.”

Students also began working with Judge Abner Mikva and Jason Huber on appellate advocacy cases. Students write briefs on behalf of clients, and third-year students argue before the appellate court. In 2005, the Appellate Advocacy Clinic got its first conviction vacated in the case of United States v. Owens. Owens had been convicted of participating in a 2002 bank robbery and had been sentenced to 145 months in prison.

In 2002, Jeff Leslie arrived at Mandel to open the Housing Initiative, which represents individuals, community-based developers, tenant groups, and others involved in the development of affordable housing.

“The project is very interesting for students,” Leslie notes. “They interact with boards and learn the angles of everyone involved. They begin to understand the challenges of communicating with a broad range of people, of understanding and explaining high-end financing, tax credits, bridge loans, and other things that are difficult even for well-educated law students to understand.”

Leslie’s project—like the Institute for Justice Clinic—created another source of transactional law experience for students. The Housing Initiative offers advice on transactional structural issues, negotiation, construction and financing contracts, zoning, and compliance issues.

In 2006, Maria Woltjen brought the Immigrant Children’s Advocacy Project to the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. Woltjen had started the project in 2004 with the support of the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Woltjen’s students work as advocates for undocumented children whose parents or legal guardians have been taken by immigration authorities. Because of the unique nature of the project, the students who work in the Immigrant Project are required to be fluent in a second language useful to the work they do—Spanish, Mandarin, Hindi, or Gujarati.

The current immigration laws do not recognize children as different from adults in regard to the immigration issue—something of growing importance, as more and more children are traveling to the United States alone. Students meet weekly at a North Side shelter with children they represent, but a large amount of the work they do is related to research and writing on advocacy on behalf of all immigrant children.

The newest project to open at the Clinic is the Exoneration Project, which represents clients who have been convicted of crimes of which they are innocent, opened in late 2007. Students working on the Project work in both state and federal courts, and are involved in all aspects of post-conviction litigation, including evaluating cases, developing evidence of innocence, filing petitions, and making motions for forensic testing.

In 2001, after ten years as director of the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic, Randolph Stone stepped down and Mark Heyrman was hired as temporary director.

“They told me it would just be for a year,” Heyrman notes, “but it turned into six.” In 2007, Heyrman handed the reins to Randall Schmidt.

“It was his turn,” Heyrman says with a smile.

As the Clinic continues its odyssey, the emphasis on student participation and involvement remains the focus of the program.

“Hopefully, one day, we will have a big enough program that we can take all of the students who want to be here,” Stone remarks.

But until then, the lottery will remain in place and the faculty will create more innovative programs to help not just the people of the South Side, but those who need help everywhere. Students will leave the Clinic with incomparable experiences and their view of law will be unalterably widened.

“One of the things we did when we celebrated our twenty-fifth anniversary was that we gave out coffee mugs with a list of all the cases we had won and the changes we had made,” Schmidt says. “And at fifty years, we spent our time talking about how well we are educating our students, about how we had gone from being a Clinic that pretty much represented anyone who came through the door to one that tries to take cases because they are projects that provide an education to our students. That change in focus is very important. In fact, that change is what the Clinic is all about now.”