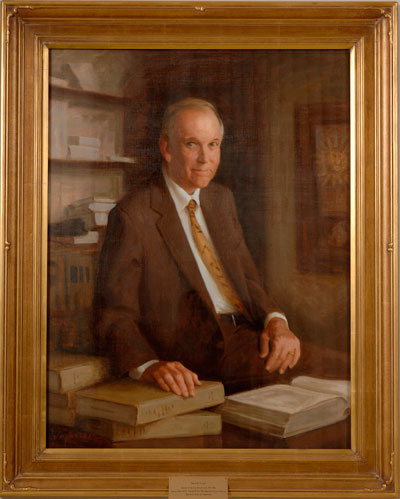

David Park Currie, 1936-2007

When David Currie passed away on October 15, 2007, the loss to the Law School community was immeasurable. David Currie joined our faculty in 1962 and, despite his “retirement” two years ago, remained a vibrant part of the faculty to the very end. He served on the faculty for longer than anyone except Edward Levi, and his impact on generations of students and colleagues cannot be overestimated.

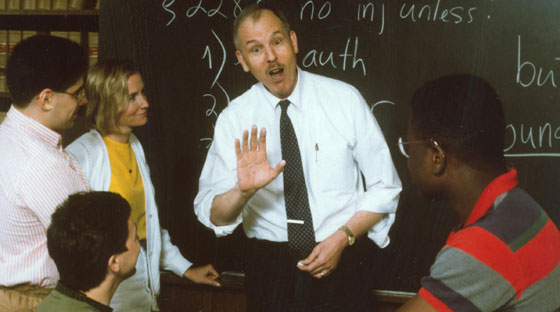

David Currie’s professional history is well known to most readers – architect of three major casebooks; expert in American and German constitutional law, conflict of laws, and pollution law, master of the Socratic method; and author of two seminal book series, The Constitution in the Supreme Court and The Constitution in Congress, just to mention a few items. His students will remember in-class performances of his beloved Gilbert & Sullivan tunes, the copy of the Constitution he always kept in his suit pocket, his love for bicycling through Hyde Park, and the twinkle in his eye. He will live on in all our memories as a true scholar, professor, and gentleman.

His academic publications are available in many places for those who wish to refresh their memories of them, but his academic work was only one part of David’s life. Those who attended his memorial service at the Law School got to know facets of David Currie that his students rarely glimpsed. Tales were told of David Currie the father, the brother, the husband, the friend. There was music as well, including a flute sonata played by his daughter, Margaret Currie. Many alumni have expressed regret that they could not attend, so here we reprint a few of the talks given that day. Others, those by his professional colleagues, will be available in a future issue of the University of Chicago Law Review.

Reverend Bernard Brown – David’s friend

We have been welcomed here in this favored place to remember together one who was a friend, a colleague, and member of a many-splendored family, much loved by him, Professor David Currie.

Our truehearted remembering allows us to draw thoughts from the many different places where his life touched our own. For my part, I remember a man I have known for thirty-five years, who from the first, as a fellow player on the stage, enlarged my awareness of a trust that must be extended to another person upon whom one depends. David was always right there with the right cue and the right timing. Moreover, he communicated a heartening expectation, bordering on certainty, that we could accomplish something together worthy of Sir William Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan.

Our truehearted remembering allows us to draw thoughts from the many different places where his life touched our own. For my part, I remember a man I have known for thirty-five years, who from the first, as a fellow player on the stage, enlarged my awareness of a trust that must be extended to another person upon whom one depends. David was always right there with the right cue and the right timing. Moreover, he communicated a heartening expectation, bordering on certainty, that we could accomplish something together worthy of Sir William Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan.

It was a splendid feeling to have done something well with David Currie, and a wonderful means of establishing a friendship that lasted these many years. Surely it was a gift of trust that inspired the remarkable veneration by David’s students, and enabled them to flourish in a demanding profession.

In the years that have so quickly passed, David and I never again worked together, but would consult on the occasions we met, regularly so, each year at a splendid Christmas party. There we sang and found out what one another was doing. I learned one year that David was writing about the constitution of West Germany. Another year it was the constitution of the Confederate States of the American southland. Earlier he spoke of his worry over the way Roe vs. Wade had been written, suggesting problems that would follow. And always he told of the increasing excellence of the Gilbert and Sullivan Company’s work year by year.

David was entirely resolved to live fully in the time left to him, in the manner that he always had done - teaching and eventually completing a spring seminar, traveling in the summer months with his family to favorite natural sites where they vigorously enjoyed the out-of-doors. He continued to attend performances of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Lyric Opera, even rising from his hospital bed in the last days to see and hear La Traviata. I hope it was a performance worthy of the man who came that night with high expectations.

Most of all, his words to me these last months testified to the bond of trust within his family that was implicit in their love for one another, for which David was surely the key to its depth and perseverance.

Elliott Currie – David’s brother

If I had to think of one word that could describe who David was, I would say that he was first and foremost a craftsman: a craftsman in the best and deepest sense. Meaning not only that he could create things with great skill and integrity, but that he held certain bone-deep values about doing the important things well and doing them right—about making the best use of your own capacities and the materials you had. David applied those values not just to one or two things, but to all the things that he truly cared about in life--his writing: his teaching: his acting: his canoeing…and much, much else.

He was naturally talented in many ways—good at a lot of things. But that isn’t what made him stand out, or what made him such a powerful inspiration—to me, and to so many of us. It was what he did with what he had.

To me, one of the most vivid expressions of that quality involved baseball. I played a lot of baseball with David when we were kids. He had an inborn talent, especially in the outfield. Those of you who knew David only after his leg and his arm stopped working right might find it hard to envision how he was in the field. But he was graceful and fast and coordinated, and pretty impressive even as a kid.

To me, one of the most vivid expressions of that quality involved baseball. I played a lot of baseball with David when we were kids. He had an inborn talent, especially in the outfield. Those of you who knew David only after his leg and his arm stopped working right might find it hard to envision how he was in the field. But he was graceful and fast and coordinated, and pretty impressive even as a kid.

But he didn’t rest there. Instead, almost as soon as it was humanly possible to get out in the field and play ball in the spring, when the snow was practically still on the ground, he’d be out shagging flies in Jackman Field, with whoever would hit a ball to him. And he did that weekend after weekend, summer after summer—he’d be out there reeling in those fly balls until someone had to come out and drag him home for dinner. And after he’d been out there summer after summer, he was no longer just a pretty good natural outfielder. He was a very good outfielder indeed. I used to think that he looked like Joe DiMaggio out there, and that’s not entirely a kid brother’s youthful exaggeration. He had made himself really very good. He had taken the materials he had and he had worked them and worked them…until he had made something that transcended what he was before.

And he did the same with so many things. He’d insist on figuring out the best way of doing something and then teach himself to do it, and he would work on it until he got it as close to right as he could. If you didn’t know him better you might think it was just a natural facility—a talent. But it was always more than that. It was craft. It was commitment. It was dedication to the job at hand.

And what’s so remarkable is that he stuck with those values even after it became much harder for him to do some of the things he had been naturally good at. Even after he had become terribly ill he continued to insist on doing what he could with what he had. If he could manage to take a walk around the Point, he would take a walk around the Point. If he could only walk halfway down the block on Harper Avenue, he’d walk that half block, until he couldn’t walk any farther. If he could get on his bike and ride over to Jackson Park, he’d get on it. And he would do the best he could. And if it took him half an hour to get dressed and ready to get on the bike or take that walk, he’d do it anyway.

I won’t say it didn’t faze him: I won’t say it didn’t bother him. I know that being limited in what he could do bothered him terribly. He was not a guy who accepted limitations easily. But the point is that it didn’t stop him.

I can’t begin to tell you how often that relentless determination inspired me—and helped me get past rough spots in my own life, big and small. You know the saying about how the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton: well, many of the battles I won in my life were won on the playing fields of Hyde Park—and in the bungalows of Santa Monica—and they were won, more often than not, because of those values that I learned from my brother’s example.

I’ll give you a small but telling instance of that. A couple of years ago I went with my family to a dude ranch in Arizona where one of the activities you could get involved in was trail bike riding—getting on a bicycle and negotiating the desert on a tiny little narrow trail through the rocks and the cactus and up and down hills. I signed up for what was billed as a “beginning” lesson, but quickly began to think I’d made a huge mistake. I was first of all easily thirty years older than the next oldest person in the group. And the instructor was some sort of manic speed demon who also seemed to be about a third my age. So after half an hour or so of huffing and puffing and falling over and getting bruised and feeling both frightened and humiliated, and seeing the backs of my fellow bikers receding yet again into the distance while I panted behind, I began to think, well, this is ridiculous: maybe it’s time to just pack it in and go home.

And then this vivid, vivid image flashed in my mind: my brother, pedaling along ahead of me in Jackson Park, teetering precariously from side to side—struggling, at this point, not only with his bum leg but now with a terminal disease. It was not the most elegant bike riding you’d ever seen, but he was doing it. And I said to myself, well, by God, if that man can keep riding his bike under those circumstances, then I can sure as hell finish this stupid trail ride. And I did--with a great sense of exhilaration and accomplishment. Though I did finish about five minutes (well, maybe ten) after everybody else.

Multiply that by several dozen times and you get some idea of how David’s example powered me through times when I might otherwise have quit, or let something slide, or just not put all of myself into a task that I knew was important.

And the power of that example, if anything, grew even stronger toward the end of his life. No one who saw him in his last years could fail to be inspired and moved—even astonished—at how fully he lived, at how he just kept on being David Currie—the same David Currie whose strength and craftsmanship and integrity had always inspired and encouraged and prodded us.

He showed us that it’s possible to face devastating illness, and the certainty of dying too soon, with grace, with engagement, with an unfading commitment to work and family--even with humor: and to do that all the way to the very end. This is, after all, the guy who, one hour after being discharged from the hospital, for the last time he would leave it alive, was in his seat at the opera watching La Traviata.

Of all the many lessons I learned from this master craftsman, that last one may be the most important. I think that when someone close to us dies, we are forced inevitably to confront our own essential fragility, our own mortality. Watching how my brother dealt with his mortality has made me less fearful of confronting my own. He taught me so much about living for so many years: in the end, he has taught me so much about dying. What an extraordinary lesson that is. What an extraordinary gift that was. What an extraordinary guy he was.

Stephen Currie – David’s son

As you’ve heard from the other speakers this morning, my father was a man of many interests, passions, and talents. You’ve heard about his love of classical music and his knowledge of the law, his commitment to his teaching and his affinity for performing. Here are a few other passions and interests that I knew about as a child and as an adult: bicycling, hiking, birdwatching, canoeing, postcards, sailboats, maps, storytelling, baseball, and languages. It’s not an exhaustive list.

As you’ve heard from the other speakers this morning, my father was a man of many interests, passions, and talents. You’ve heard about his love of classical music and his knowledge of the law, his commitment to his teaching and his affinity for performing. Here are a few other passions and interests that I knew about as a child and as an adult: bicycling, hiking, birdwatching, canoeing, postcards, sailboats, maps, storytelling, baseball, and languages. It’s not an exhaustive list.

I don’t want to give the impression, however, that my father was interested in everything. He wasn’t. It often seemed that Dad was either passionate and knowledgeable about a given subject or an activity, or he knew nothing about it and cared less, and the borderline was sometimes mighty thin. He enjoyed novels, especially those written in German or French, as long as they were published before about World War II. He loved music---through about the time of Puccini. My wife and I once gave him a CD of a tenor singing the works of Sigmund Romberg, Victor Herbert, and other operetta composers he loved. When we asked how he liked it, he looked pained and replied, “Oh, the man takes unconscionable liberties with those songs.”

It was great for me when my interests coincided with those of my father. For example, I love to kayak, I loved our trips to Wrigley Field, even if he did root for the wrong team, and I know almost as much geographic trivia as he did. (I do hate sailing, however.) Sometimes, though, my interests fell into the other category. That was true of, oh, the Hardy Boys books, say, or the TV show Rocky and Bullwinkle. I developed an interest in soccer at one point and in the music of Elvis Presley at another. Dad dismissed soccer, half-jokingly, as a “commie pinko sport” and Elvis, not jokingly at all, as “the man singlehandedly responsible for the downfall of Western civilization.”

Then again, Dad wasn’t entirely predictable. He very much enjoyed both To Kill a Mockingbird and Catcher in the Rye, though I’m not entirely sure what possessed him to read either of these “modern” novels. When I was about ten, he brought home a record of a jazz group called the Firehouse Five Plus Two; it was a little incongruous next to the Brahms symphonies that made up our usual listening fare.

Then there was the time a few years back when I found myself with a free afternoon in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia on a beautiful sunshiny day in early spring. I wasn’t sure whether to take a hike or to visit one of several caverns in the area that promised sound-and-light shows and rock formations that resembled Nativity scenes. So I asked myself, “What would Dad do?” The answer was breathtakingly obvious—he would go for a hike. He would grab a canteen and a map and a pair of binoculars and head up a mountain trail, exclaiming “Glorious!” at every bird, every crag, every vista. (“Glorious” was the operative word whenever he hiked.) There was, I reasoned, no chance that dad would spend a beautiful sunshiny spring afternoon below the ground, among tacky sound and light shows and rock formations that looked vaguely like the baby Jesus.

Then there was the time a few years back when I found myself with a free afternoon in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia on a beautiful sunshiny day in early spring. I wasn’t sure whether to take a hike or to visit one of several caverns in the area that promised sound-and-light shows and rock formations that resembled Nativity scenes. So I asked myself, “What would Dad do?” The answer was breathtakingly obvious—he would go for a hike. He would grab a canteen and a map and a pair of binoculars and head up a mountain trail, exclaiming “Glorious!” at every bird, every crag, every vista. (“Glorious” was the operative word whenever he hiked.) There was, I reasoned, no chance that dad would spend a beautiful sunshiny spring afternoon below the ground, among tacky sound and light shows and rock formations that looked vaguely like the baby Jesus.

So of course I went to the cave. And I had a wonderful time, but that’s not the point of the story, for when I talked to Dad later on he asked me if I had gone to a town called Luray when I was in the Shenandoah Valley. Yes, I said, why do you ask? Well, Dad explained, when he had been a boy his family had visited a large cave there called Luray Caverns, and he had loved it, and just recently, he continued, he had gone to Washington and had driven into the Shenandoah Valley specifically so he could visit Luray Caverns all over again—and it was just as glorious, he added, as it had been when he was ten.

There are lots of morals in this story, I suppose, morals about parents and children, morals about predictability, morals about the folly of thinking that you really understand what makes someone tick. The moral I’d like to draw out today, though, is a little different. My dad experienced many “dangers, toils, and snares,” especially in his last years, but he always seemed to agree with Piglet that the first thing you should say when you wake up in the morning is “I wonder what’s going to happen exciting today?” When I think of my father, I think of a man who was always involved in something that sustained and intrigued him—a man constantly on the lookout for the glorious things of the world, a man who found glorious things wherever he looked. Though he used the word “glorious” mainly to describe things in nature, I believe that he found it glorious as well to spend an evening with a fascinating pre-World War II novel , glorious in another way to come up with an interesting new interpretation of the Constitution, and glorious yet again to put together a Gilbert and Sullivan production. He found glory, of course, in taking a hike on a sunshiny spring day in the Shenandoah hills—and in spending that same sunshiny day on an adventure a hundred feet below the ground. And to him, the future was distinctly glorious as well: in his appreciation for his students on the one hand, and for his children, his grandchildren, and his many nieces and nephews on the other. To look for the glory in the world, in all the world—in the natural world, in the world of ideas, in the world of people—is a remarkable thing, and a thing worth trying to emulate; and to my mind, the ability to see that glory wherever he looked might have been my father’s greatest legacy.

Reverend Bernard Brown

I understand that a venerable tradition exists in this School of Law for the students to salute their professor at the end of an excellent term of teaching with a standing ovation. (I have to say that I know of nothing like this happening in the Divinity School.) Here in closing such an expression is needed from all of us, who in one way or another, have been David’s students. In remembrance of the life of this remarkable man, scholar and teacher, I judge it to be fitting and proper that we show our appreciation in the way to which he had become accustomed.

[a standing and rousing ovation followed]