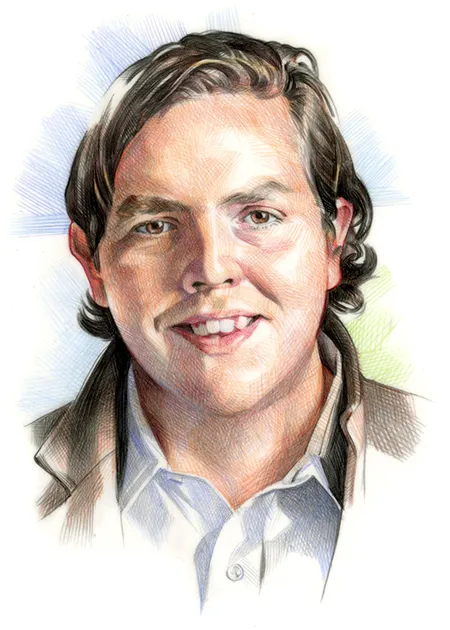

At the Center of a Supreme Court Case

William Baude, Harry Kalven Jr. Professor of Law, made international headlines earlier this year when a law review article he coauthored provided a basis for Colorado to argue in Trump v. Anderson that former President Donald Trump be removed from the 2024 presidential ballot.

“The Sweep and Force of Section Three” amassed more than 100,000 downloads and 350,000 views on SSRN in just a few months of it being published— numbers that are virtually unheard of. The paper, coauthored by Michael Stokes Paulsen from the University of St. Thomas School of Law, concluded that Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment bars previously elected officials from holding office if they participate in an insurrection.

Baude, well known for his expertise on constitutional law and originalism, argued in the article that Section Three is self-executing and should operate as an immediate disqualification from office, without additional action by Congress.

The idea caught on. According to the tracking efforts of the New York Times, before SCOTUS rejected Baude and Paulsen’s theory, thirty-six states formally challenged Trump’s candidacy based on the insurrection clause. Colorado was one of the first states to do so when six voters brought suit that Trump should be disqualified from the state’s Republican primary. The Colorado district court ruled that Trump could not be barred, but the Colorado Supreme Court decided he could. The Colorado Republican party then appealed to the US Supreme Court.

Law School alumnus Jonathan Mitchell, ’01, represented Trump in court. During oral arguments, both he and Justice Elena Kagan acknowledged that Baude’s analysis of a key precedent—called Griffin’s case—was contrary to Mitchell’s. From the oral argument transcript:

Mr. Mitchell: Yeah, there certainly is some tension, Justice Kagan, and some commentators have pointed this out. Professor Baude and Professor Paulson criticized Griffin’s Case very sharply.

Justice Kagan: Then I must be right. (Laughter.)

Despite Kagan’s quip that Baude’s argument might be right, the Supreme Court ultimately disagreed and ruled that states lack the power to enforce Section Three against federally elected officials.

“After I listened to the oral argument, I was not surprised by the holding, because the questions the justices asked during the oral arguments made clear the court was looking for a way out of letting Colorado disqualify Trump from the ballot,” Baude said.

The path the court chose surprised Baude, however, because it wasn’t the focus of any of the eighty amicus briefs that had been filed.

“I took this as a sign of how badly they wanted to get out and how hard it was to get out,” he said. “Where there are suspicions of politics, the court works extra hard to try to find a consensus ground, even if that consensus is not the first choice of many of the justices.” Baude and Paulsen have already written another article that is forthcoming in the Harvard Law Review— “Sweeping Section Three under the Rug”—analyzing and criticizing the court’s decision.

Whether you agree with Baude’s constitutional interpretation or the Supreme Court ruling, the fact that one of Baude’s articles was at the epicenter of one of the most closely watched and hotly contested cases of the term demonstrates the sheer impact of his scholarship.

Generally viewed as a conservative legal scholar, Baude is often tapped by both sides of the political spectrum and debates with other law professors on all sorts of constitutional law issues. A graduate of Yale Law School, he began his career clerking for Justice John G. Roberts and then, in 2021, was a member of the Biden administration’s Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court.

Although he is one of the country’s most knowledgeable scholars of Supreme Court history, Baude believes it is not his place to tell students whether to criticize or laud the Supreme Court as an institution. Instead, he says his job is to understand the arguments that lead to the court’s holdings so that he in turn can teach them. He is adamant that to understand complicated ideas, one must examine the different sides and be able to argue them, and one of his goals as a professor is to model how to do that.

“I think a big challenge of teaching constitutional law today is not the Supreme Court but legal academia,” he said. “Law professors should resist the pull of politics and ask if we can maintain the perspective necessary to teach effectively about the court and the Constitution.”

One way to build and maintain that perspective is to debate ideas, which is why in 2020, Baude formed the Constitutional Law Institute. Through it, thousands of students, listeners, and readers have been introduced to constitutional history and law. By writing scholarship, lecturing, and leading participatory lunch talks and conferences, Baude explores ideas with other scholars, many of whom disagree with him politically.

“Where there are suspicions of politics, the Court works extra hard to try to find a consensus ground …”

Prof. William Baude

“We strive to be intellectual, not political, and I think this is really important given that constitutional law has become an increasingly polarized field,” Baude said. “We value ideas based on their content rather than who articulates them.”

The past four years have allowed Baude to put some of his theories into practice, and the law review article about disqualification was a prime example of how a complicated legal theory can be debated by brilliant legal minds that disagree.

Meanwhile, the most popular lunch talk the institute has hosted was not in the least related to current events. It was a discussion with Visiting Professor Jud Campbell (now at Stanford Law School) of the deep theoretical question about the role of natural rights, which is not pending in any Supreme Court case.

“It was standing room only in one of our biggest classrooms,” Baude said. “There is a hunger for learning about complex issues outside the political arena.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article misstated the graduation year of Jonathan Mitchell. He graduated in 2001, not 2002.