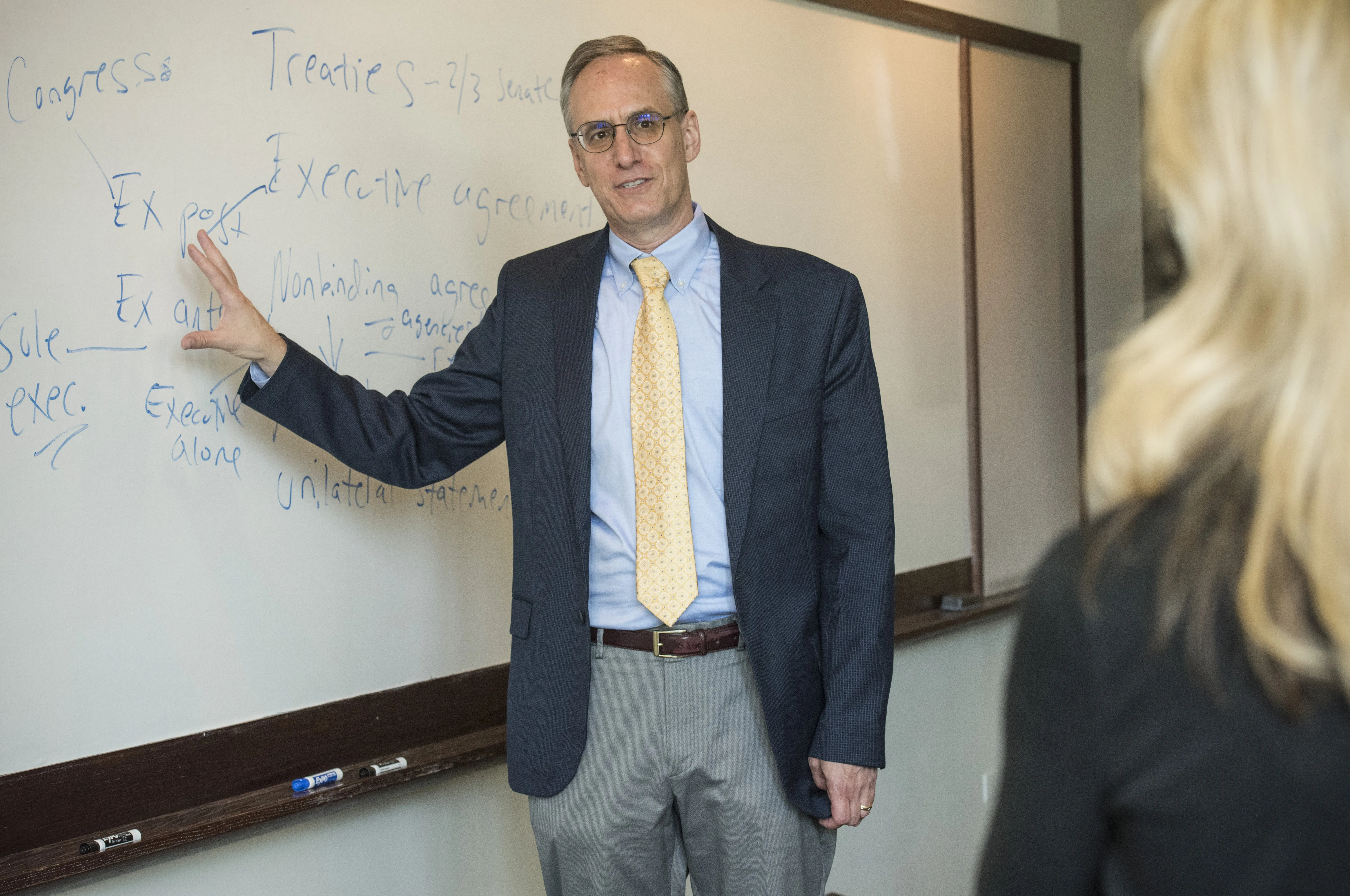

Professor Curtis Bradley, Leading Scholar of Foreign Relations Law, Joins Faculty

This is an updated version of a story that originally ran in April 2021. This version ran in the Fall 2021 issue of the Law School Record.

Professor Curtis A. Bradley, a pioneer in the study and teaching of comparative foreign relations law and an international leader in the broader field of foreign relations law, joined the Law School faculty this summer from Duke Law, where he taught for 16 years. Bradley, a prolific scholar known for his willingness to challenge conventional views, said he hopes to make the Law School a “hub for new thinking about the field of foreign relations law.”

“In my view, no other law school in the country can match the vibrancy of the University of Chicago Law School’s intellectual culture,” said Bradley, whose expertise includes international law in the US legal system, the constitutional law of foreign affairs, and federal jurisdiction. “With its roundtable discussions, intense workshops, sharing of draft work, and frequent collaborations, it is the sort of place that makes everyone there better, and I want to benefit from and contribute to the energy and ambition of the place.”

Bradley graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1988 and then clerked for Judge David Ebel of the US Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit and Justice Byron White of the US Supreme Court. Bradley most often teaches courses on foreign relations law and federal courts, areas he often connects in his scholarship. He has written or edited more than a half dozen books, including a foreign relations casebook (now in its seventh edition), a federal court casebook (now in its ninth edition), and The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Foreign Relations Law, a 900-page volume that earlier this year was awarded the American Society of International Law’s inaugural Robert E. Dalton Award for Outstanding Contribution in the Field of Foreign Relations Law. That book, which Bradley edited, grew from a global conference series he organized and which helped build the scaffolding for the emerging field of comparative foreign relations law. The project also earned him, and was funded in part by, a 2016 Carnegie Fellowship.

“Professor Bradley is an exceptionally distinguished scholar whose innovative thinking has had a tremendous influence on the field of foreign relations law,” said Dean Thomas J. Miles, the Clifton R. Musser Professor of Law and Economics. “His excellence in teaching and scholarship, his commitment to interdisciplinary collaboration, and his zeal for new ideas will make him a superb colleague on our faculty. We are delighted to welcome him to the Law School.”

Adam Chilton, who cochaired the Law School’s Appointments Committee with Professor Jennifer Nou, said he is “extremely excited that Curt Bradley has chosen to join our academic community.”

“Curt is the leading scholar of foreign relations law and his approach to research fits perfectly with the University of Chicago’s academic values: he is productive, collaborative, and willing to challenge conventional wisdom,” Chilton said. “But Curt not only has a well-earned reputation as one of the country’s leading legal scholars, he also has a reputation for being a phenomenal teacher, mentor, and community builder.”

Bradley said teaching invigorates him—and often informs his writing.

“I have had the great benefit of being able to talk through many of my scholarly ideas with students,” he said. “I think that being excited about teaching and being excited about scholarship go hand in hand.”

Bradley—whose work has been cited in numerous court decisions, including at least seven times by the US Supreme Court—writes on issues such as the war powers of Congress and the president, the making of and withdrawal from international agreements, the presidential use of emergency powers, and the status of international law within the US legal system. He has also written more broadly about how historical practice does and should inform debates surrounding these issues.

In December 2020, Bradley and two coauthors, Jack Goldsmith of Harvard Law and Oona Hathaway of Yale Law, released the results of an unprecedented empirical study that, for the first time, shed light on the system surrounding the hundreds of binding international agreements that US presidents make each year. The paper, “The Failed Transparency Regime for Executive Agreements: An Empirical and Normative Analysis,” published in the Harvard Law Review, was the product of a three-year project that involved interviews with government lawyers as well as a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit to obtain more than 5,000 documents from the US Department of State. The scholars concluded that the executive branch’s reporting to Congress has been incomplete, that the process is opaque, and that Congress is “failing in its oversight role.”

The scholars are now studying the executive branch’s growing practice of entering into nonbinding international agreements, which often fall outside of the reporting and publication requirements that Congress has imposed for binding agreements.

In September, he will cohost his first conference as a member of the Law School faculty, convening about two dozen leading scholars and government officials online to discuss national practices relating to nonbinding international agreements. The event, which is open only to the participants, aims to discern how constitutional democracies are addressing these agreements within their domestic legal systems and to encourage cross-national dialogue about possible regulatory reforms.

“This is the hottest issue in comparative foreign relations law right now,” said Bradley, as nations are struggling “to preserve the flexibility that these agreements allow while also ensuring that there is sufficient coordination and transparency in the commitments that are being made by executive officials.”

In addition, Bradley, who also writes on federal courts, is the coauthor of a forthcoming Yale Law Journal article, “Unpacking Third-Party Standing,” that examines when litigants should be allowed to invoke the rights of third parties, an issue that has arisen in recent challenges to both abortion and firearm restrictions.

Beginnings

Bradley, who earned his undergraduate degree in 1985 from the University of Colorado, practiced law at Arnold & Porter in Denver and, after his Supreme Court clerkship, at Covington & Burling in Washington, DC, where his work with overseas litigation clients sparked an interest in international law. At Covington & Burling, he worked with Goldsmith, who also had been a Supreme Court clerk during the 1990 term. The two became frequent collaborators.

During the first decade of his academic career, Bradley taught at the University of Colorado School of Law and, later, at the University of Virginia School of Law. In 2004, he spent a year as the “counselor on international law” in the Legal Adviser’s Office of the US State Department.

“I learned a tremendous amount in that position about how the executive branch makes decisions relating to foreign relations and how it interacts with other parts of the government,” said Bradley, who still serves on the State Department’s Advisory Committee on International Law.

In 2005, he joined Duke’s faculty, ultimately becoming the founding codirector of the Center for International and Comparative Law and serving on the executive board of Duke’s Center on Law, Ethics, and National Security.

Over the years, Bradley pushed against conventional thinking on foreign relations law, arguing, for instance, that the government’s actions in foreign affairs are not exempt from domestic constitutional considerations—an idea that has been a theme in much of his writing.

“Before [Goldsmith and I] came in, a lot of scholars in the area placed little weight on structural constitutional values—such as the interest of the states in retaining some regulatory autonomy,” Bradley said. “The idea was basically that once you get to foreign affairs, the Constitution’s concerns about separation of powers and federalism should either go away or become greatly diminished—and I started pushing against that in a series of papers, and I coined a term to describe it.”

That term, foreign affairs exceptionalism, is now commonly used in foreign affairs law scholarship.

Developing a New Field

Between 2012 and 2018, Bradley also worked as a reporter on the American Law Institute’s influential fourth Restatement of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States, a successor to the third Restatement that had been published in 1987. Early in his career, Bradley criticized aspects of the third Restatement, and he was delighted by the opportunity to work on the fourth Restatement, which he called “a privilege.”

As part of that process, the group sought the perspectives of scholars and government officials from other countries—and the experience deepened Bradley’s appreciation for the value of comparative study.

“It got me thinking pretty quickly that a lot of constitutional democracies are struggling with some of the same foreign relations law questions we are in the US,” he said.

Although scholars—including Tom Ginsburg, the Law School’s Leo Spitz Professor of International Law—were engaged in comparative work on general issues of constitutional law, there was “no sustained thinking about how to do that in foreign relations law,” Bradley said.

So, in 2015, Bradley launched a series of conferences that brought together leading foreign relations law scholars from around the world. He applied for, and won, $200,000 in funding through a prestigious Andrew Carnegie Fellowship and held events in Japan, South Africa, and Europe. Those symposia led to The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Foreign Relations Law, which was published in July 2019. It contains 46 chapters that include empirically focused research, theoretical work, and in-depth case studies representing a variety of perspectives. (Ginsburg is among the contributors.)

“In the first section of this book [we explore]: What is foreign relations law? What is comparative foreign relations law? How do you study it as a scholar? And to my delight, there are different views about that in the book,” Bradley said. “What’s exciting is that we don’t have to agree exactly how to define the field or even where it should go. My hope was just to get it started.”

Bradley said collaboration and debate have always been essential to his scholarly work. He describes himself as “a big conference person,” and said the University of Chicago’s emphasis on both interdisciplinarity and varied perspectives were a big part of what drew him the Law School.

“That is how you get genuine innovation in ideas,” he said. “The prospect of being a part of that innovative community is enormously appealing to me.”