'A Watershed Era in the Evolution of Accountability'

Study by the Law School's Sharon Fairley Shows Police Oversight Agencies Growing Across US, but Challenges Persist

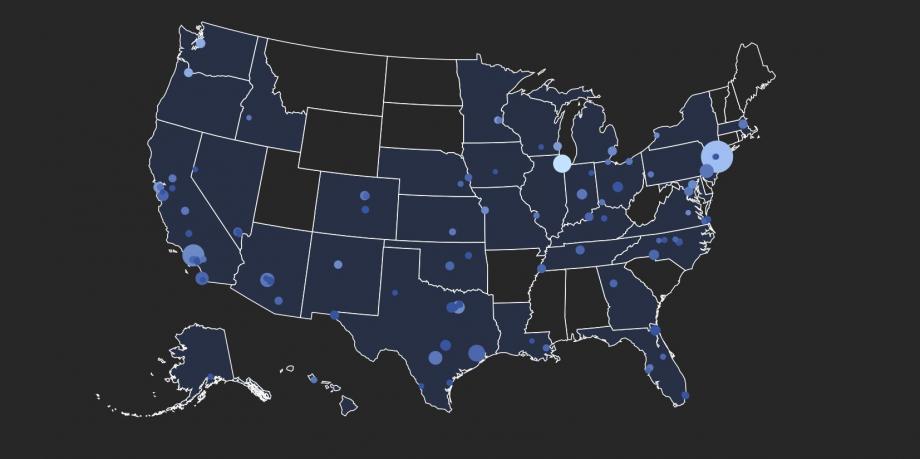

Amid growing public outcry over police use of force, new systems for police accountability and public oversight have taken root in cities across the country over the past five years. That’s the key finding of new research from University of Chicago Law School Professor from Practice Sharon R. Fairley, who in 2019 surveyed the 100 largest cities in the United States. While tensions persist among police, politicians, and the public, the results point to what she called a “watershed era in the evolution of accountability,” as more cities respond to community demands by starting new civilian oversight bodies or enhancing the powers of existing ones.

Her study, Survey Says?:U.S. Cities Double Down on Civilian Oversight of Police Despite Challenges and Controversy, is published in de•novo, the online journal of the Cardozo Law Review, and is accompanied by an interactive website where visitors can learn about the civilian oversight agencies operating in each of the 100 cities, including the oversight functions they provide, a description of their mission, and the year they were formed.

“Civilian oversight is no longer experimental, it is mainstream,” said Fairley, a leading scholar on police accountability. “But, there are still problems of resources and independence. Oversight structures are often the product of political compromise between stakeholders who support the concept of independent oversight on the one hand and those who question the legitimacy of it and seek to limit its impact on the other. You need the community to trust the process.”

Too often, she said, she sees a pattern: “scandal, reform, repeat.”

While the principles of civilian oversight can be traced back a century, Fairley’s research, a comprehensive review of the challenges and opportunities facing today’s police accountability systems, finds that the impetus for the recent growth and sophistication of civilian oversight is often tied to controversial police use-of-force incidents.

A former federal prosecutor with the United States Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois, Fairley led efforts to reform police oversight in Chicago in the wake of the 2014 murder by police of Laquan McDonald. She was appointed to serve as the chief administrator of the Independent Police Review Authority, the agency responsible for police misconduct investigations, and was also responsible for creating and building Chicago's new Civilian Office of Police Accountability. That work informed her views on the importance of integrity, transparency, and independence of oversight agencies.

“To fulfill their mission, they have to have power to influence the system,” she said. The creation of multi-tiered oversight systems, like that of Chicago—which is comprised of three separate and distinct oversight bodies—adds complexity and opportunity for conflict to arise.

A key challenge facing civilian oversight entities today is the ability to satisfy community concerns that the accountability processes are fair and neutral while also withstanding challenges made by police unions, police officials, and police organizations who discount the judgment of civilian oversight professionals. The issue of neutrality engendered particularly contentious debate in Chicago over whether the new oversight agency should be able to hire investigators with prior law enforcement experience. Ultimately, a compromise was reached and the agency is barred from hiring only those who worked for the Chicago Police Department in the preceding five years.

Among the civilian oversight entities created in the past five years, many have similarly chosen to restrict hiring or appointing members with prior law enforcement experience by law. The Civilian Oversight Board in St. Louis allows only one of its seven board members to have previously been "a commissioned employee of any municipal, state, or federal law enforcement agency."

Other steps that can enhance the odds for success:

- Sustainability. Even some of the oldest oversight entities in the United States continue to face skepticism about the quality of the oversight they provide. Many US cities are becoming more cognizant of the need to create sustainable systems that can withstand the scandal/debate/repeat cycles that are bound to occur over time. For example, New York’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, one of the longest standing agencies, continues to spark criticism. The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) recently claimed the agency has failed to fulfill its mission because it has been unable to establish an effective investigative operation, and failed to advocate effectively for reform of police practices that pose a risk to public safety.

- Subpoena power. A major source of debate is the power to compel both law enforcement and civilian witnesses to provide information essential to the investigatory process and relevant in the review and appeals of oversight.

- Budgetary independence. Lack of resources can undermine the thoroughness and timeliness of investigations. The budget for the Albuquerque Civilian Police Oversight Agency must be at least one-half of 1 percent of the budget for the police department. In Chicago, the budget floor for the Civilian Office of Police Accountability was set at one percent of the Chicago Police Department’s budget.

- Transparency. Crucial to building trust with the community, public reporting can be a challenge. Houston’s Independent Police Oversight Board has been criticized for not publicly announcing its findings, so citizens have no way of knowing whether the board ever disagreed with the police department in a disciplinary matter. But, as Fairley noted, the extent to which oversight agencies report on their process and findings is often constrained by local and state law.

Fairley commended the work of four cities in particular: Seattle, Washington; Oakland, California; Austin, Texas; and Newark, New Jersey.

“Seattle and Oakland have completely revamped their systems in the last two years, each creating a robust, multi-agency approach,” she said. “Both these cities appear to have recognized the need for a comprehensive solution.”

Seattle passed historic legislation creating a new multi-faceted accountability structure, including enhancing the existing Office of Police Accountability, making the Community Police Commission a permanent fixture, and adding the new role of Inspector General for Public Safety. Oakland created a new police commission with the power to oversee the police department by reviewing and proposing changes to department policies and procedures, and with the authority to terminate the chief of police for cause without the approval of the mayor.

In addition, “Austin has done a good job of doing their homework before leaping forward with a plan,” Fairley said. “They have studied the issue and have been very transparent about how they are going about the process of building the system there.” In 2018, the city began dismantling its police oversight infrastructure after the city auditor found that the citizen oversight, in place since 2001, had not created substantive change within the Austin Police Department, largely due to city procedures and police department practices. Austin now is putting plans in place to remake its oversight based on “best practices.”

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, Fairley said, “Newark has done a great job of standing strong in the face of challenges and roadblocks thrown up by the police union.” Amid Department of Justice findings of serious deficiencies in the police department’s accountability system and a pattern of constitutional violations in the stop and arrest practices, the city created a new oversight agency in 2016, but it has been bogged down ever since by legal action from the police union.

The research concludes with a call for greater focus on evaluating the effectiveness of civilian oversight, including the cost-benefit tradeoffs of civilian oversight, to help municipalities better assess options and design systems that best suit their needs.