Dark Patterns: Can Consumers Break Out?

Editor’s Note: This story is part of an occasional series on research projects currently in the works at the Law School.

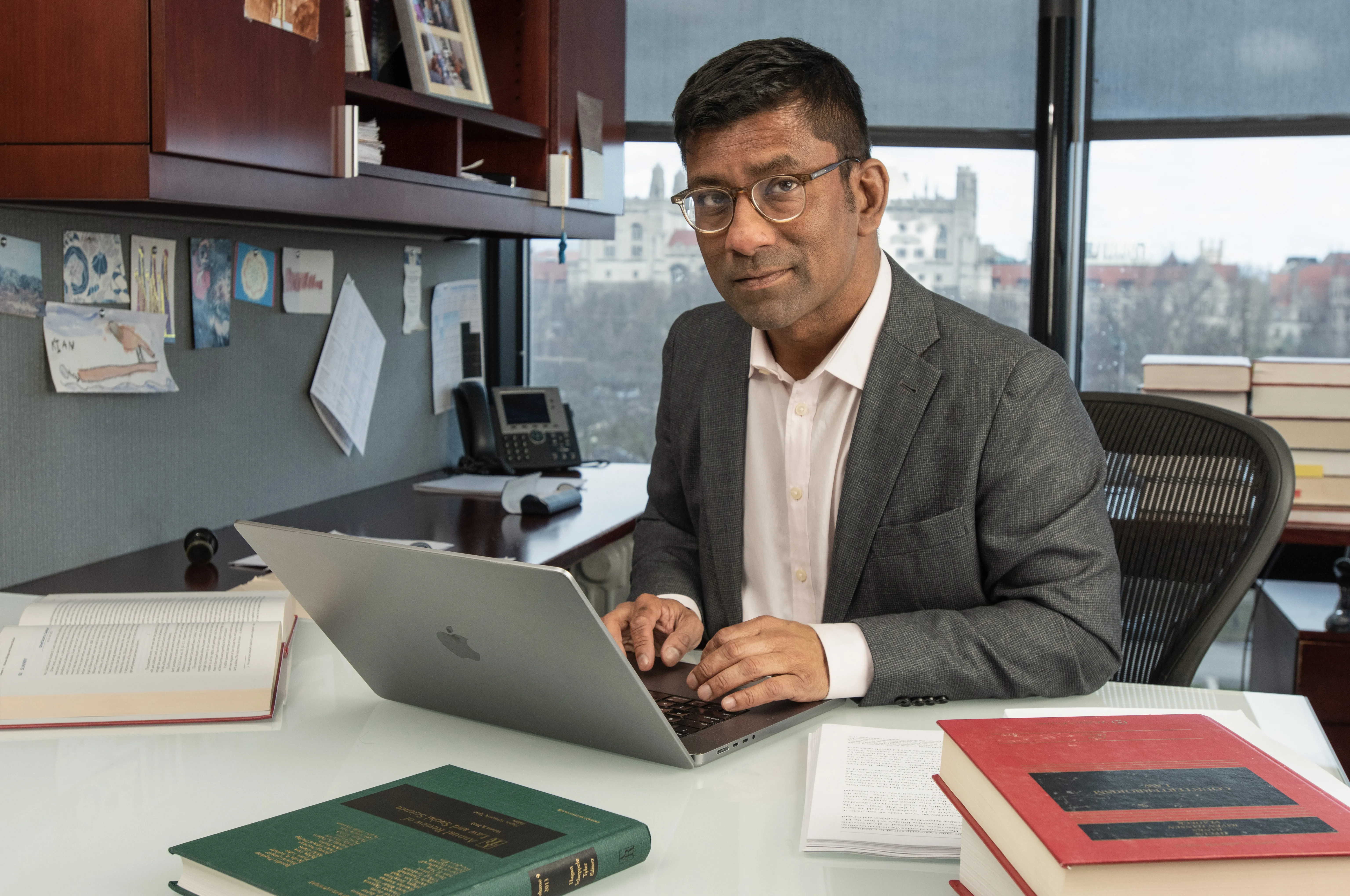

Lior Strahilevitz coauthored a highly influential 2021 paper that illuminated the legal and policy challenges posed by “dark patterns”—manipulative online tactics designed to trick consumers into making purchases or surrendering their data. In the years since that groundbreaking work helped shape public discourse, these deceptive practices have not only persisted but also evolved, becoming increasingly sophisticated and leaving consumers more frustrated than ever.

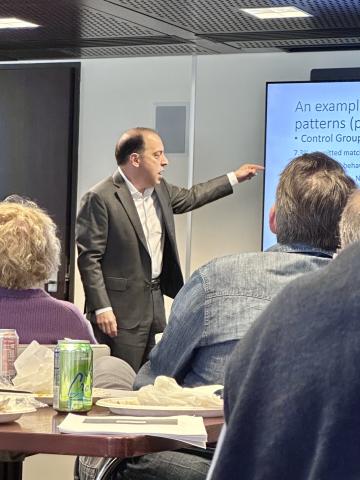

In his newest paper, Strahilevitz, the Sidley Austin Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, revisits dark patterns, this time exploring potential solutions. His cutting-edge work took him into experimental settings and interdisciplinary collaborations. Working with computer science and social psychology experts, he even helped develop a fake, but convincingly realistic, Netflix-like video streaming platform to test how consumers respond to manipulative interfaces under real-world conditions.

“The nature of social science research is that whenever you answer one question, it opens up five more,” Strahilevitz explained of his decision to revisit dark patterns. “Even after waiting a few years and seeing other scholars advance the field, there were still critical, unresolved questions I felt compelled to tackle.”

One key question centered on the effectiveness of dark patterns in persuading individuals to surrender private information. “That issue had been studied experimentally, but primarily in cookie consent interfaces,” Strahilevitz said. “We wanted to create a much richer, more organic experimental environment—one that mirrors real-world conditions more accurately. We were also particularly interested in whether dark patterns are more effective when people are under cognitive load, meaning they’re distracted or multitasking.”

These inquiries culminated in the paper, “Can Consumers Protect Themselves Against Dark Patterns?” Coauthored with Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Professor Matthew Kugler, ’15, (who also has a PhD in social psychology from Princeton), University of Chicago Associate Professor of Computer Science Marshini Chetty, and Chirag Mahapatra, a graduate student at Harvard, the work exemplifies UChicago’s distinctive approach to interdisciplinary and empirical scholarship.

Shining a Light

Strahilevitz coauthored his first paper on dark patterns, “Shining a Light on Dark Patterns,” with Jamie Luguri, ’19, a former student who also holds a PhD in psychology from Yale. That paper, which was also empirical in nature, used a clever experimental design to demonstrate the power of dark patterns: many respondents were tricked into inadvertently signing up for identity-theft protection services they didn’t want. While the respondents believed their money was at stake, no payments were ever taken, and they were fully debriefed at the conclusion of the experiment.

Users exposed to aggressive dark patterns were more than four times as likely to subscribe to the fake identity-protection service compared to those who were not. Even exposure to milder dark patterns doubled the likelihood of sign-up.

When the first draft was posted online in 2019, the pathbreaking paper was the first scholarship to empirically demonstrate the effectiveness of dark patterns, and it cemented Strahilevitz’s status as a leading authority on the issue. He quickly became a go-to resource for policymakers, advising the Federal Trade Commission, California privacy regulators, and the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority, among others.

“The paper ended up being more impactful, both in the United States and around the world, than anything else I’ve ever written,” Strahilevitz said in a 2022 Law School article highlighting his work. “Sometimes the best scholarship comes from feeling like there’s a problem in the world that folks are starting to notice but nobody is collecting the data.”

Seeking More Answers

The new paper was aimed at answering two key questions about dark patterns: Do they influence choices consumers make when selecting privacy settings, and, if so, does that influence persist even when consumers actively seek to protect their privacy?

More than 1,700 participants were recruited for the experiment, a sample that mirrored the demographics of the US adult population. They were asked to sign up for a video streaming website to beta test it. The sign-up process provided them with a series of six privacy choices similar to the kinds of decisions consumers face when joining new digital platforms. Some participants were exposed to various dark patterns during the sign-up process, while others were not.

Before beginning the sign-up process, half the participants were assigned a privacy goal. Instead of signing up as they normally would, they were instructed to make the most privacy-protective choices throughout the process. The other half were told to choose the privacy settings they would ordinarily select when signing up for a new video streaming service.

The website itself appeared authentic, displaying actual movie titles and artwork. Participants encountered various options involving data collection and privacy, such as enabling personalized ads, allowing cookies, opting out of the sale and sharing of their personal information, and other familiar choices. The interface some participants saw deployed a nagging dark pattern, where they were repeatedly prompted to reconsider privacy-protective choices they had made earlier. Other participants saw dark patterns that made critical information less visually prominent, switched the default choice to less privacy protective options, or required extra mouse clicks from subjects who tried to protect their privacy compared with those who didn’t.

The results were striking. Across the board, dark patterns successfully manipulated participants into making privacy decisions they otherwise would not have chosen—including those who had been explicitly advised to be mindful of their privacy.

“Several dark patterns influenced participants as they completed an account set-up procedure that closely mirrored what consumers might encounter if signing up for a new video streaming service like Netflix, Hulu, or Peacock,” the paper says. “This paper strongly suggests that dark patterns do prompt consumers to surrender more privacy than they otherwise would.”

Moreover, the study found that dark patterns adversely affect a wide range of consumers: rich and poor, young and old, men and women, and individuals across the educational spectrum.

“The biggest takeaway is that, even when people are told, ‘Hey, your goal here is to protect your privacy,’ for a large segment of the population, dark patterns are going to thwart their ability to do so,” Strahilevitz said. “I think that strengthens the case for some form of regulation in this area.”

Looking Ahead

Despite now having two papers under his belt on the topic, Strahilevitz is far from finished putting a spotlight on dark patterns. He is currently working with an interdisciplinary team on another paper to determine whether California privacy regulations that he helped craft to combat dark patterns have reduced the prevalence of dark patterns there. The researchers have found that the regulations are working, but companies are exploiting gaps in the regulatory framework and developing new kinds of dark patterns that regulators didn’t anticipate.

“I'm generally supportive of the need for regulatory intervention here, but there is always a cost to industry, and you want to see whether the regulations are having the desired impact and justify the cost,” he said.

This kind of research aligns perfectly with Strahilevitz’s empirical outlook. “It's really fun to get data and learn something about the world and then share that with scholars and policymakers, and people who work at these companies,” he said. “I think in a lot of these spaces that I write about, especially law and technology, the world just needs more facts.”

Read the Research Paper: