The Cartoonists’ Guide to Law

The D’Angelo Law Library’s New Collection of Illustrated Legal Codes Offers Insight into Statutes and Society

At first glance, the cartoon in the French law book on Lyonette Louis-Jacques’s desk in the D’Angelo Law Library seems almost funny, in a banana-peel-pratfall kind of way.

For starters, there’s actually a banana peel in the picture, two slippery slivers making their mischief beneath the foot of a well-dressed redhead. She’s knocking her elbow back protectively as she tumbles—skirt lifting, purse flying—into the man beside her. Like a domino, he’s pitching forward, his hands thrust outward and his chapeau tossed upward.

Comedy, right? Except the scene is meant to depict involontairement un homicide, which means that someone is about to die—and someone else is unintentionally at fault. It seems likely that the man is the one mortally doomed; his lurch has propelled him toward a third pedestrian—and directly into the sharp tip of a walking cane. Worse, the instrument has dislodged his eye, which is now impaled on its tip like a campfire marshmallow.

“It took me a while to realize that this guy’s cane was poking through this other guy’s eye,” Louis-Jacques, the D’Angelo Law Library’s foreign and international law librarian, said. “There’s so much going on here.”

So much, in fact, that the accident’s cause—and the proper distribution of blame—is unclear, which seems both puzzling and appropriate for a drawing that is accompanied by a French description of involuntary manslaughter and the accompanying criminal penalties.

This, of course, is part of the intrigue.

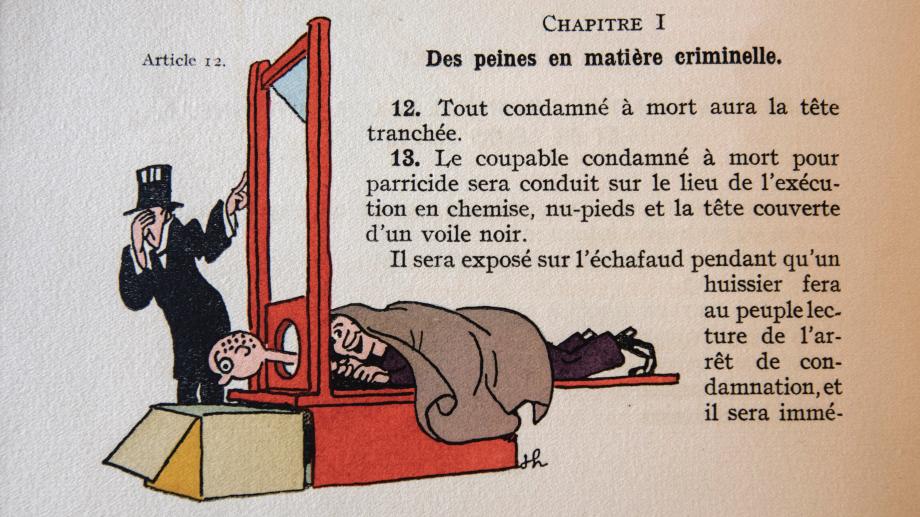

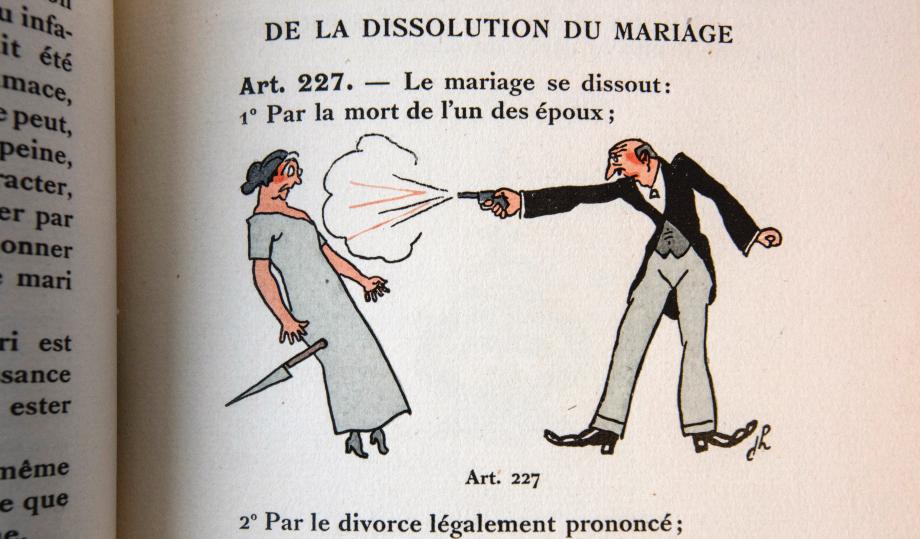

The book, published in Paris in about 1929, is an illustrated copy of the French criminal code by the early-20th-century cartoonist Joseph Hémard, who was popular at the time. And Louis-Jacques, who was drawn to the visual and humorous mode of interpreting law, had worked particularly hard to find it. It now resides in the D’Angelo’s new and growing collection of illustrated law books. The Code pénal, like other Hémard books that she’s acquired—including the Code civil, an illustrated French civil code published in 1925, and the Code général des impôts directs et taxes assimilées, a lengthy, illustrated French tax code published in 1944—is rife with nuance, social commentary, and a depiction of the law that transcends language and culture.

“It’s a way of telling stories about the law and opening up people’s minds,” said Louis-Jacques, who became interested in the genre when she saw a rare books display featuring some of Hémard’s work at a conference. “The illustrations are humorous, and sometimes they’re scandalous, and often they’re thought-provoking.”

She loved the idea that the illustrations might start a conversation or pique a student’s interest in an area of law, and she was intrigued by their ability to express both the happenstance of the human condition and the complexity of law.

Take, for instance, the scene with the skewered eye. Assuming the tumbling man is the one to expire, who bears responsibility for his death? The woman, for clumsily pushing him into the cane? An unknown, or unseen, banana eater, for dropping the peel? The man with the cane, for brandishing his walking aid so recklessly?

“Look at this guy’s nose,” Louis-Jacques said, pointing to the cane bearer’s flushed face and reddened nose. “Is he drunk? Is that why he’s unaware? And look at the woman—who’s responsible if she dies?”

And what if the scene is meant to be understood in reverse, with the cane, rather than the peel, setting everything in motion? What if the cane has propelled the injured man backward, into the woman and toward the banana peel? And what if the man with the cane is actually drunk? What if he only appears to be drunk? What if they’re all drunk?

“These illustrations do more than show the code,” Louis-Jacques said. “They take it a bit further; they show an understanding of how complicated the law can be.”

Which is what makes them such a welcome addition to the library’s collection, D’Angelo Law Library Director Sheri Lewis said.

“Understanding the story behind a legal question is essential for interpreting and applying the law,” Lewis said. “While law books are filled with such stories, they very rarely include illustrations that depict the legal situations discussed. These rare books offer a unique and colorful way for a reader to connect with the law. We are delighted to have them in our collection.”

So far, the D’Angelo’s collection of cartoon-illustrated law books is small—there are only about a dozen—because finding them isn’t always easy.

“They aren’t always described in a way we can easily call up,” Louis-Jacques said. “They aren’t usually listed as ‘cartoon-illustrated law codes.’ There is the subheading ‘caricatures and cartoons’, but that is rarely added to law books in the library catalog unless expressly requested.”

Law books, she added, aren’t generally illustrated, so it’s easy to overlook the illustrations unless they are well integrated into the text, as the Hémard books are.

Right now, the collection is anchored by the Hémard volumes, although Louis-Jacques has also acquired a French traffic code, the Code de la route, and a French tax code, the Code des impôts, both published in the late 1950s and illustrated by Albert Dubout, as well as more recent volumes like Le nouveau code pénal illustré (The new illustrated penal code), which was illustrated by Francis Le Gunehec and published in 1996. There’s also a 1944 volume illustrated by Hémard and authored by the celebrated French writer Honoré de Balzac, titled the Code des gens honnêtes, ou l’art de ne pas être dupe des fripons (roughly translated as the Code of honest people, or the art of not being tricked by swindlers).

“That’s not a law code—it’s a behavior code aimed at gentlemen of the time,” Louis-Jacques said. “Balzac wrote it in 1845 and then Hémard illustrated it in 1944. There were only 800 copies made and the D’Angelo has one of them.”

There are many others Louis-Jacques hopes to acquire—an illustrated Brazilian penal code and an illustrated French tourism code among them—and she enjoys blending her language and research skills to hunt for the volumes, waiting to see if one ends up listed on a library sale or an estate auction.

Eventually, she hopes to create an exhibit that offers additional context for the volumes, including historical information about the illustrators and the time periods in which they were published. She’s curious whether Hémard’s own biases and prior experiences—and even his lack of legal training—might have influenced his interpretation of the law and his artistic choices.

The works, she notes, make the law accessible by appealing to universal themes. In the Code civil, there’s a cartoon depicting a woman trying hard to keep a man from running toward another woman; one doesn’t need to read French to recognize the depiction of marital infidelity. In the tax code book—the volume for which Hémard was most famous—a worried-looking man runs from a judge.

“This is tax law in France, but there are the same sort of issues and the same sort of attempts to avoid paying taxes,” Louis-Jacques said with a laugh.

And then there’s simply the ability of the books to lure one into thinking about the law.

Louis-Jacques held up a plain book and a copy of the Code pénal, which features on its cover a colorful cartoon of a man with an axe in his head pointing at a man with a smoking gun who appears to be fleeing winged creatures, one of whom is carrying the scales of justice.

“If I showed you both of these,” she said, displaying both, “which one are you more likely to open?”