Preserving the Texture of Legal History: The Pleasure and Privilege of Rare Books

On the D’Angelo Law Library’s sixth floor, behind the glass walls and the keycard-entry doors, bathed in air that is always between 60–65°F and 45–60 percent humidity, are the really old books.

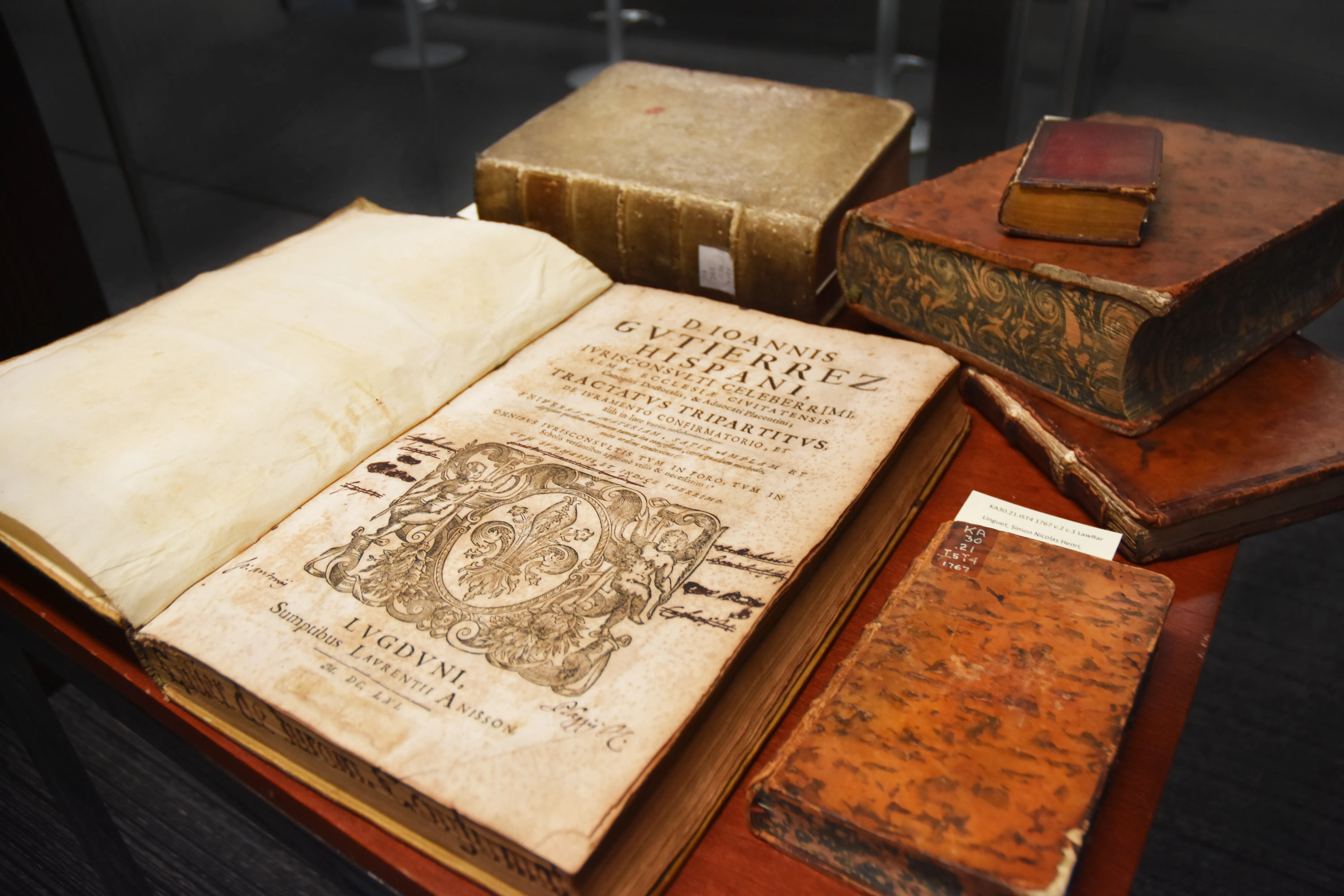

The artifacts sit in this climate-controlled silence, brought out for the occasional visitor but more often viewed digitally by students and scholars who might never have cradled a 400-year-old calfskin volume or turned a heavy parchment page printed in calligraphy. There are more than 3,700 items in the Law School’s collection, and more than half are available in digital form—meaning those volumes are both physically rare and more accessible than ever before. It is a modern paradox: as technology brings content closer—and reduces the need for in-person use—does a rare book become more so, or less? Can it be both?

Digitization of rare te xts has been an important development—scanned books are accessible to a greater number of researchers and are searchable—but it is impossible to fully replicate the experience of working with an original. The process of converting the documents into searchable text isn’t perfect; abbreviations, for instance, aren’t always translated consistently or accurately. Context can be lost if a full volume isn’t available and one can’t flip back to find a full citation or foundational details. And the experience of holding and reading a physical volume is lost when it appears only on a screen. To visit the two rooms housing the D’Angelo Law Library’s Rare Books Collection—or better, to thumb through a centuries-old volume beside a historian like Alison LaCroix, the Robert Newton Reid Professor of Law, or R.H. Helmholz, the Ruth Wyatt Rosenson Distinguished Service Professor of Law—is to peer into the lives and minds of the long-gone scholars and leaders who created our nation’s governing structure, or interpreted canon law, or commented on the decisions of a 17th-century European court. It is to touch what they touched, to see the law in a slightly different way, and to remember that all of these ideas were created and shaped by people.

xts has been an important development—scanned books are accessible to a greater number of researchers and are searchable—but it is impossible to fully replicate the experience of working with an original. The process of converting the documents into searchable text isn’t perfect; abbreviations, for instance, aren’t always translated consistently or accurately. Context can be lost if a full volume isn’t available and one can’t flip back to find a full citation or foundational details. And the experience of holding and reading a physical volume is lost when it appears only on a screen. To visit the two rooms housing the D’Angelo Law Library’s Rare Books Collection—or better, to thumb through a centuries-old volume beside a historian like Alison LaCroix, the Robert Newton Reid Professor of Law, or R.H. Helmholz, the Ruth Wyatt Rosenson Distinguished Service Professor of Law—is to peer into the lives and minds of the long-gone scholars and leaders who created our nation’s governing structure, or interpreted canon law, or commented on the decisions of a 17th-century European court. It is to touch what they touched, to see the law in a slightly different way, and to remember that all of these ideas were created and shaped by people.

It is, simply, to feel the curves and coils of history.

***

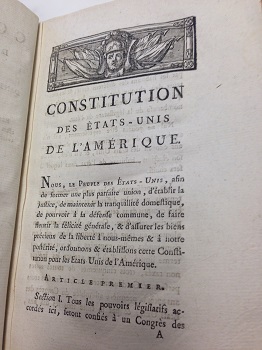

One afternoon last fall, LaCroix held some of these curves and coils in her hand—a 225-year-old, first-edition French translation of the United States Constitution and acts of the first U.S. Congress that the D’Angelo acquired about two years ago. The book, Actes passés à un congrès des Etats-Unis de l'Amérique, is believed to be the first French translation of the Bill of Rights and is curious for any number of reasons, not the least of which is that it essentially groups the nation’s supreme law alongside things like the Tariff Act of 1789.

“We don’t usually think of the Constitution as an act of Congress—it’s not just some regular old statute,” LaCroix said. “But there it is.”

Then there’s the puzzle of the book’s origin, a question made somehow more compelling by the volume’s physical presence. The text was translated by one Monsieur Hubert, who appears to have been a lawyer or judge in the French parliament, or court—but who asked Monsieur Hubert to do it? And what might that decision tell us about the America’s efforts to gain recognition on the world stage, Europe’s view of the fledgling democracy, or early U.S. political divisions? What clues might lurk in the volume’s marginalia, or the ways in which the content is structured? The timing makes it intriguing: the late 1780s brought not just the ratification of the U.S. Constitution but the start of the French Revolution, a 10-year conflict that inspired both enthusiasm and fear among Americans. There was marked division in America—those who were pro-British and those, like Thomas Jefferson, who were pro-French. Had someone in America thought it important to share our law with the French during their time of upheaval, or had someone in France requested it?

Then there’s the puzzle of the book’s origin, a question made somehow more compelling by the volume’s physical presence. The text was translated by one Monsieur Hubert, who appears to have been a lawyer or judge in the French parliament, or court—but who asked Monsieur Hubert to do it? And what might that decision tell us about the America’s efforts to gain recognition on the world stage, Europe’s view of the fledgling democracy, or early U.S. political divisions? What clues might lurk in the volume’s marginalia, or the ways in which the content is structured? The timing makes it intriguing: the late 1780s brought not just the ratification of the U.S. Constitution but the start of the French Revolution, a 10-year conflict that inspired both enthusiasm and fear among Americans. There was marked division in America—those who were pro-British and those, like Thomas Jefferson, who were pro-French. Had someone in America thought it important to share our law with the French during their time of upheaval, or had someone in France requested it?

“Who was the audience? Who in France said, ‘I want the U.S. Constitution and I want to know what the U.S. Congress is doing?’” LaCroix said. “As often happens when you pick up a primary source, all these question arise.”

As she turned the pages, history seemed to swell and take shape: there, in French, was the Judiciary Act of 1789, which would eventually become the first congressional act to be partially invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court. But when it was translated for this volume, the act was still new and whole: it would be more than a decade before the landmark Marbury v. Madison struck down one of its provisions, affirming the concept of judicial review.

“When we’re talking about these periods in law school, it doesn’t always seem concrete: it is Marbury v. Madison, it is John Adams and George Washington and their theories. They’re in casebooks, so the texture is stripped away,” LaCroix said. “But there is so much literal texture in this volume: just feeling the pages and seeing the print. It’s a mode of human connection with people who created the structures of government institutions and offices.”

She ran her finger down a page, examining the text as she spoke.

“These were things that were created by people,” she continued, “let’s not forget that.”

***

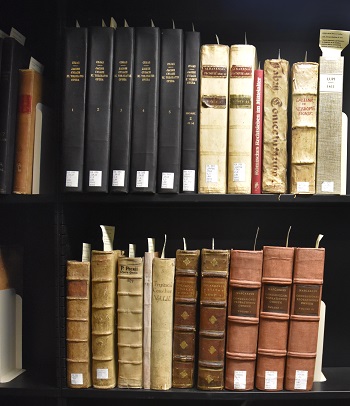

The strength of the D’Angelo’s Rare Books Collection is historical U.S. law; the D’Angelo has nearly all the original primary sources in that category. The library is working to expand the European collection, an important area of growth, D’Angelo Law Library Director Sheri Lewis said. Right now, the library adds at least a few rare materials each year, and acquisitions are often driven by opportunity. Librarians—often Lyonette Louis-Jacques, Foreign and International Law Librarian, and Bill Schwesig, Bibliographer for Common Law—peruse dealer catalogs, participate in rare book auctions, and look for other chances to acquire volumes that meet particular research interests or add valuable dimension to the collection. In the autumn of 2014, for instance, the D’Angelo acquired about 100 rare titles that had been withdrawn from the collection at the Rutgers School of Law-Camden Law Library.

The vast majority of the D’Angelo’s rare books are from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though fourteen percent are from the seventeenth century and four percent are from sixteenth century. There are early volumes of the United States Reports, sixteenth-century canon law written in Latin, and volumes of Consilia, which are collections of opinions written to advise European judges in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and early eighteenth centuries. There are books on Prussian law, materials on witchcraft trials, and volumes of Sir William Blackstone’s eighteenth-century Commentaries on the Laws of England, which are influential treatises that played a role in the development of the American legal system. Some of the books in the D’Angelo’s rare collection are heavy elephant folios; others are just a few inches long, small enough to fit in the palm of a hand. Many of the books are beautiful, featuring ornate, handset type or fore-edge painting, which are designs or pictures painted onto the edges of the pages. Some have elegant, handwritten notes in the margins—the insights of early readers. Some volumes have held up surprisingly well for their age, and others have been rebound or preserved in other ways.

The vast majority of the D’Angelo’s rare books are from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though fourteen percent are from the seventeenth century and four percent are from sixteenth century. There are early volumes of the United States Reports, sixteenth-century canon law written in Latin, and volumes of Consilia, which are collections of opinions written to advise European judges in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and early eighteenth centuries. There are books on Prussian law, materials on witchcraft trials, and volumes of Sir William Blackstone’s eighteenth-century Commentaries on the Laws of England, which are influential treatises that played a role in the development of the American legal system. Some of the books in the D’Angelo’s rare collection are heavy elephant folios; others are just a few inches long, small enough to fit in the palm of a hand. Many of the books are beautiful, featuring ornate, handset type or fore-edge painting, which are designs or pictures painted onto the edges of the pages. Some have elegant, handwritten notes in the margins—the insights of early readers. Some volumes have held up surprisingly well for their age, and others have been rebound or preserved in other ways.

“Our library is fortunate to have these treasures of law and legal history in our collection,” Lewis said. “Our aspiration is to grow; there are still scholars who work with this material, and they work with it in a way that makes the actual artifact desirable.”

After all, not everything has been digitized; books that aren’t available online—especially ones that fit faculty research interests—are of obvious and particular value. The first-edition French translation of the Constitution, for instance, was a title the library knew LaCroix would appreciate. When the library acquired it, the book was in pamphlet form, and they took it to a rare book conservator to have it rebound.

D’Angelo librarians often consult with Helmholz, the rare book collection’s most frequent user. Right now, he’s hoping to help them find a collection of volumes published near the end of the sixteenth century: Tractatus universi iuris, or “The Treatise of All Laws.”

“It was a standard book, and we don’t have a copy, but we should,” he said. “It’s proving a little hard to find one, but it’s the kind of thing I’d like to get.”

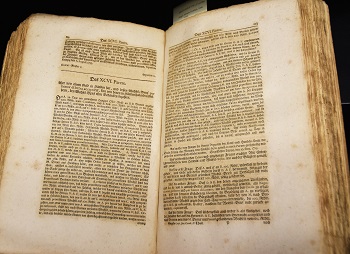

A scholar whose expertise includes canon law, Helmholz has his own collection of rare books in his office and at home—though none, he notes, are on the extreme end of rare or valuable. For instance, there’s a 1556 volume covering basic canon law of the Middle Ages that he got a bit of a deal on.

“It’s quite a handsome volume, but look at this,” he said, flipping through the inside, “it was lacking some of the pages. So what the book dealer did is Xerox from another edition and paste these in. It’s a far-from-perfect copy—even the title page is gone, and the binding isn’t in great shape. But it’s useful, and for my purposes, it works. And I was able to buy it for, I don’t remember, maybe $400.”

Students and others who visit Helmholz’s office will sometimes ask about the books, and he usually doesn’t mind pulling a volume or two from the shelf. It’s gratifying, he said, to see the interest.

“Pick one out,” he told a visitor one morning last fall, before offering a brief tour of a heavy 1709 volume detailing the duties of ecclesiastical judges. “Did you have any Latin?” he asked the visitor—who hadn’t—before translating some  of the text and encouraging her to be less hesitant in turning and touching the pages.

of the text and encouraging her to be less hesitant in turning and touching the pages.

“They’re not fragile—you can see this is done in rag paper,” he said. “These things will still be around when most of the books we have from the 1900s are dust.”

This is another part of the draw: many old books are durable, a tribute to the craftsmanship of their time. They’re also practical in ways that digital versions are not. In any book, for instance, one can stumble upon related content or deliberately flip back a few pages for context. A rare book might represent the only opportunity to do that within a given niche.

“If you pull up a statute online and you’re in a small subset—small Roman numeral iv, part 3—you don’t know where you are,” LaCroix said. “As an intellectual matter, you need to be able to work back up the tree and see what’s next to it.”

Optical Character Recognition, the technology that converts the books to searchable documents, can fall short, particularly in dealing with abbreviations in Latin or other foreign languages.

“By experience, you can work out what these abbreviations mean, but you can’t really search for them,” Helmholz said. “Some of the sources cited in rare books become quite unrecognizable in scanned versions. Normally, in rare books, scanned versions are not adequate substitutes for the original.”

As these volumes continue to become both older and more accessible, Helmholz wonders if the market might offer an advantage to those who are still after the physical experience of the old book.

“My hope is that prices [of rare books] will decline markedly so we can buy more. I haven’t seen evidence of that yet, but it is my hope,” he said. “If you can get what you need in digitized form, why would you pay a small fortune for a book—except for the pleasure or privilege of having a rare book and being able to look at it?”